Introduction

This paper aims to discuss how Orientalism is

described in Ulysses.

Leopold Bloom has a Hungarian Jewish background, although he was born

and raised in Dublin. Hungary is often described as the country

built up as a powerful empire by the Asian leader Attila the Hun in the

early fifth century. According to the Bible, the early ancestors

of Jews had lived as tillers of the soil or nomads around Mesopotamia,

were taken away to Egypt as slaves, and settled in Israel experiencing

the Babylonian captivity until the Roman Diaspora. Also, some

people have believed that the Celts originally came from Central

Asia. Bloom is portrayed as an East Asian by J.J. OfMolloy, the

fallen barrister:

"His submission is that he is of Mongolian extraction and irresponsible

for his actions" (U

15.954-55). This defense sounds like a disdain to Mongolians,

motivated by racial prejudices.

Molly observes that [He sleeps] "like that

Indian god he took me to show one wet Sunday in the museum in Kildare

street" (U

18.1201-2). So Bloom has multiple Asian aspects, although

all of his Asian elements are subtle and impalpable.

Contemporary Irish writers including W.B.

Yeats, George Russell and James Stephen got involved in the Irish

Literary Renaissance and many of them were interested in the Orient as

well as Theosophy. In "Lotus Eaters" Bloom's Orientalism is

featured. Under the British rule, Ireland had a two-sided

attitude toward the Orient from a postcolonial perspective.

Bloom's point of view also seems inconsistent with the Orient

throughout the novel. Referring to the arguments of Edward Said's

Orientalism and Joseph

Lennon's Irish Orientalism,

Bloom's ambivalence about the Orient will be examined.

I.

Orienting Orientalism

Europe was fundamentally created by the Roman Empire first with their

overwhelming force, and later with Christianity. When the

empirefs power gradually declined, they manipulated Christianity to

unify their far-reaching territory. Needless to say, Christianity

was authored by Jesus of Nazareth and, after his symbolic crucified

death, it was founded by Paul the Apostle, another gprotestanth Jew,

and was widely propagandized by his disciples across the Mediterranean

Sea after the Roman armyfs destruction of the Second Temple of

Jerusalem in AD 70 when orthodox Jews excluded Jesusfs Jewish

followers, the Nazarenes. In 313, the struggles of the early

Church were lessened by the legalization of Christianity by the Emperor

Constantine I. In 380, Christianity became the official religion of the

Roman Empire by the decree of the Emperor Flavius Theodosius. The

ancient Roman Church decided to include the Hebrew Scriptures as the

first part of the Bible in which the Ancient Middle East or the Orient

is described, although the Christian Bible divides and orders the

collection of the Hebrew Scriptures differently, and varies from

Judaism in interpretation, etc. Since then, Christians have been

familiar with the history and folklores of Jews as described in the

Bible. The more they practiced Christianity, the more they hated

the Jews whose ancestors crucified Jesus as a heretic. It was

Jews who have lived in the boundary between the Orient and Europe,

between the East and the West. In other words, Jews created the

division between the two worlds. Since the Middle Ages, Jews have been

seen in the Western world as both Occidental and Oriental. Jews formed

the model for medieval depictions of Muslim warriors in the Age of the

Crusades.

In the Italian lecture gIreland, Island of

Sagesh in 1907, Joyce regarded the Irish language as Oriental: hThis

language is oriental in origin, and has been identified by many

philologists with the ancient language of the Phoenicians, the

originators of trade and navigationh (CW

156). Ireland had been invaded by foreigners many times before

the English rule. Joyce tried in the lecture to separate the

uniqueness of Irish language and culture from (especially British)

invadersf showing his vague longing for the Orient.

As Edward Said argues, it is Orientalism, a

style of thought about the Arabs, Islam, and the Middle East, that

primarily originated in England, France, and then the United States,

and that actually creates a divide between the East and the West (Said

2). His examples depict the West as culturally superior to the East.

This "Western superiority" became politically useful when France and

Britain conquered and colonized "Eastern/Oriental" countries such as

Egypt, India, Algeria and others: gin short,@Orientalism as a Western

style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the

Orienth (Said 3).1 Orientalism is

part of the Western

culture and

a by-product of Imperialism.

Said summarized his work in these terms:

My contention is that Orientalism is fundamentally a political doctrine

willed over the Orient

because the Orient was weaker than the West,

which elided the Orientfs difference with

its weakness. . . . As a

cultural apparatus Orientalism is all aggression, activity, judgment,

will-to-truth, and knowledge. (Said 204)

If you replace the words gOrient/Orientalismh with gCelt/Celticismh in

Saidfs argument, it makes almost the same sense in postcolonial

Ireland. Irelandfs colonial status was rather complex because it

suffered from British Imperialism while it also benefited some as a

part of the British Empire until the early twentieth century, as, for

instance, many statues of the reclining Buddha in the National Museum

indicate.2 Joyce, Bloom and Molly

just saw one of them

on

display.

Joseph Lennon developed Saidfs idea in the

case of Ireland in his book Irish

Orientalism. Lennon's self-defense begins early,

suggesting his study "runs the risk of also being dismissed as the

latest in a long series of illogical discussions about connections

between the Oriental and the Celt" (Lennon xix). gBut the goal of

this work is not to reassert the legendary Oriental origins of the

Irishh (Lennon xix). Irish Orientalism proceeds in two distinct

parts. The first part mines the history of Irish Orientalism as a

discourse. The second part considers the Irish Revival period as

a culmination, of sorts, of Irish writersf response to the East.

Lennon discusses Orientalism/Celticism of numerous writers such as

Diodorus Siculus, the ninth-century Irish monk, Dicuil, Edmund Spenser,

Thomas Moore, W.B. Yeats and James Cousins.

When was Joyce conscious of the Orient

first? As Heyward Ehrlich notes, Joyce wrote two biographical

essays on the Irish Orientalist James Clarence Mangan in 1902 and

1907. gAraby,h which Joyce wrote in Trieste in 1905, evokes the

characteristic version of Irish Orientalism gthat looked to the East

for the highest sources of national identity and the very origins of

the Irish language, alphabet, and peopleh (Ehrlich 309). Joyce

was familiar with Irish Orientalism in Dublin, thanks to his friends

including W. B. Yeats and George Russell who indulged in Theosophy, and

Triestefs exotic flavor induced him to the Orient further.

Trieste was an important port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It

was located on the border between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, or

more precisely, between Europe (familiar to Joyce) and the "Orient"

(strange or exotic to him) in Edward Said's definition.3

As John

McCourt notes: gFor Trieste was in two crucial ways an Oriental

workshop for Joyce. Firstly, it genuinely contained aspects of

Eastern countries, in its population, its culture and its architecture;

and secondly, it actively partook in the creation and maintenance of

standard Western stereo-typical visions of the Easth (McCourt

41). Among numerous Oriental motifs Buddhism/Hinduism played an

important and significant role in Joycefs works because he was first

familiar with Orientalism through Theosophy.

For Joyce, the Jews are an "Oriental"

people. It was the Jews that gave him the eastern exotic

mood. The census of 1910 revealed that Trieste had 5,495 Jews

(McCourt 222). He first wrote about a Jewish young lady in

Giacomo Joyce in the cityfs

exotic mood.4 It was a

good practice

for him to write about the Jews. He developed the theme of

Orientalism in Ulysses to

describe the protagonist Bloom as a man with

the Hungarian Jewish background. Later in the final chapter of

Finnegans Wake, his

inclination to the Orient finally reached the Far

East where China and Japan were at war in the late 1930s.5

In Trieste, a port city of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire, Joyce was presumably interested in the unique

history of Hungary. It is often said to have been founded by the

Asian leader Attila the Hun in the early fifth century, following a

Celtic (after c. 450 BC) and a Roman (9 BC-c. 4th century)

period. In fact, Attila the Hun was erroneously regarded as an

ancestral ruler of the Hungarians. It is believed that the origin

of

the name "Hungary" does not come from the Central Asian nomadic

invaders called the Huns, but rather originated from the seventh

century, when Magyar tribes were part of a Bulgar alliance called

On-Ogour, which in Old Turkish meant "(the) Ten Arrows."6

Hungary was founded by Arpad the Magyar leader in 896 when the Magyars

arrived in the Carpathian Basin. Hungary was established as a Christian

kingdom under St. Stephen I, who was crowned in December 1000 AD in the

capital, Esztergom. Later Stephen I was canonized and became the

guardian saint of Hungary. Presumably Joyce also liked the

coincidence that the guardian saint of Austria is St. Leopold.

II.gCalypso,h

the Mirus Bazaar and gLotus-Eatersh

Joyce

never visited any of the key gOrientalh

countries that figure in Ulysses,

Hungary, Palestine and Spain, but

Joyce drew on elements from all of their cultures gto create truly

hybrid characters – Leopold and Molly Bloomh (McCourt 42).7

Gerty

McDowell notices Bloom as gthat foreign gentlemanh (U 13.1301) and

Bloom also remembers Mollyfs answer to his question gWhy me?

Because you were so foreign from the othersh (U 13.1209-10).

Bloom is reported in gIthacah to have a gfull build, olive complexion,

may have since grown a beardh (U

17.2003). His reported height

g5f9h (U 17.2003), and gweight

of eleven stone and four poundsh [158

pounds] (U 17.91) proves

Joycefs disbelief in the stereotype of Jewish

shortness. Bloom looks like a foreigner in Dublin, but not always

Jewish. As Bloom explains to Stephen, his wife Molly is

half-Spanish, born in Gibraltar. She has the Spanish type, gQuite

dark, regular brunette, blackh (U

16.876-81). Bloom has a

Hungarian Ashkenazi background and Molly seems to have a Sephardic

background. Both gOrientalh types could be often seen in Trieste

in Joycefs time.

Lennon introduces that Roderic OfFlaherty

called Ireland gOgygia,h the island where Calypso the beautiful nymph

detained Odysseus for seven years and kept him from returning to his

home of Ithaca, quoting William Camden citing Plutarch (Lennon

58/60). The Greek word gOgygiah means gprimeval,h gprimalh and

gat earliest dawnh according to A

Greek-English Lexicon by Liddell

& Scott (9 Rev Sub). gOgygiah is strangely connected to

Joycefs naming the episode gCalypsoh where Bloom, an Irish man with the

Hungarian Jewish background, eats breakfast and prepares for the

journey of the day. Molly is still in bed and later works as a

Calypso not for Bloom but for Blazes Boylan while her husband is out.

The motif of the journey to the east first

appears in the short story gArabyh of Dubliners

in which the boy

narrator goes to the special bazaar gArabyh in the mood of an Oriental

version of the Holy Grail Quest. Joyce is known to have visited

the Araby Bazaar between 14 and 19 May 1894. Homogenous bazaars

took place each year after 1892 as charity fundraising events, which

often provided people some opportunities to be familiar with Oriental

cultures. The central feature of the Araby Bazaar was its large

construction of a g[r]ealistic representation of an Oriental cityh

according to The Irish Times,

16 May 1894, 6 (Ehrlich 314). Joyce

occasionally refers throughout Ulysses

to the similar Mirus Bazaar

hosted by the viceroy Earl of Dudley in aid of funds for Mercerfs

hospital.8 Bloom sees the placard

of the bazaar near

the

Freemasonfs hall in Molesworth Street (U

8.1162). The progress of

the viceregal cavalcade for the bazaar is tracked from the Viceregal

Lodge in Phoenix Park to the Mirus Bazaar in Ballfs Bridge near

Ringsend (U 10.1176-282).9

It passes many of the people who have

appeared in gWandering Rocks.h Most of them notice, and some

salute the cavalcade.

As Lennon notes, not only Joyce but Oliver St.

John Gogarty and Samuel Beckett also lampooned misty images of the

Celts and the Orient, dismissing them as romance and indulgent fancy

(Lennon 208). This indicates that the Celtic-Oriental connection

was not the only subject for ridicule (Lennon 208). The major

entertainments of the bazaar, however, were not directly related to the

Orient, as the programme showed.10

Later that evening the bazaar fireworks provide a background for Gerty

MacDowellfs tempting encounter with Bloom on Sandymount Strand (U

13.1166-68).

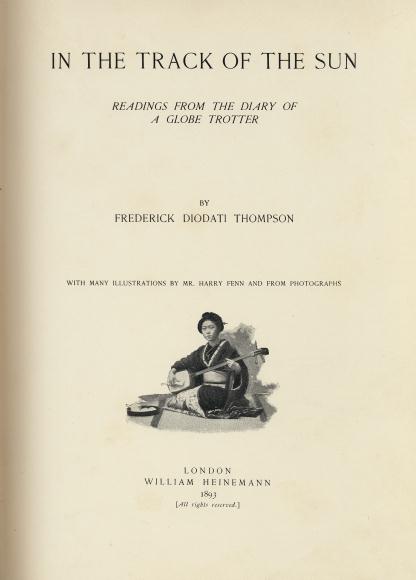

In the sunny morning scene of gCalypsoh Bloom

goes out from his apartment at 7 Eccles Street toward St. Georgefs

Church in the south (Hardwicke Place) gin the track of the sunh (U

4.99-100). Bloomfs longing for the East intimately associates

with F. D. Thompsonfs In the Track of the Sun (New York/London 1893),

which is included in Bloomfs library, although it is reported that the

title page is missing (U

17.1395). The book is Thompsonfs

itinerary of the seven-month-and-four-day globe trotting starting on

October 14, 1891\from New York to the East\Japan, China (Hong Kong and

Canton), Ceylon, India, Egypt and Palestine: Thompsonfs itinerary

roughly covers the range of Bloomfs association with the East in

gCalypsoh and gLotus Eaters.h Thompson sailed back to New York

via Europe. The book is full of attractive illustrations and

photos. The title page (recto) of In the Track of the Sun has a

photo of a Japanese girl playing the samisen as Bloom remembers: gA

girl playing one of those instruments what do you call them:

dulcimers.h (U 4.97-98).11

Bloom later associates the title with womenfs wear: gFashion part of

their charm. Just changes when you're on the track of the

secret. Except the easth (U

13.804-5).

Bloom bought a pork kidney at Dlugaczfs, whose

name implies his possible Polish Jewish background, and ate it.

Pork is of course forbidden to eat for orthodox Jews. In Buddhism

pork was reportedly the last dish for the Buddha before he entered the

Nirvana. Bloom left his apartment at 7 Eccles Street after

easement. He is in black to attend Paddy Dignamfs funeral. He

does not bring a change of clothes so he wears black all through the

day, which seems to emphasize his Jewishness. Leopold Bloomfs

journey to the east is featured in gLotus-Eaters.h

III. Bloom

the Buddhafs Orientalism

In

the opening passage of gLotus-Eatersh Bloom imagines the East on a

sunny, warm morning. In Westland Row he halts before the window

of the Belfast and Oriental Tea Company and reads a tea poster gchoice

blend, made of the finest Ceylon brandsh (U 5.18-19): he soon

associates it with gThe far east. Lovely spot it must be: the

garden of the world, big lazy leaves to float about on, cactuses,

flowery meads, snaky lianas they call them...h (U 5.29-31).

Ceylon is famous for tea products, and also the place where Henry S.

Olcott's Buddhist Catechism Joyce once owned in Dublin was compiled as

the author noted at the end of the booklet. Next Bloom imagines

the people's idle lives there like the Lotus-Eaters in the Odyssey,

gSleep six months out of twelve. Too hot to quarrel. Influence of

the climate. Lethargy. Flowers of idleness. The air

feeds most. Azotes. Hothouse in Botanic gardens.

Sensitive plants. Waterlilies. Petals too tired to.

Sleeping sickness in the airh(U

5.33-36). Next Bloom remembers

the chap in the picture gin the dead sea floating on his back, reading

a book with a parasol openh (U

5.37-39).

For a time Bloom forgets the

East while he walks westward to check his post box at Westland Row Post

Office, encounters C. P. MeCoy talking about Paddy Dignam's death, etc.

and reads Martha Clifford's letter in the lee of Westland Row Station

wall. After finishing it, he resumes his walk and reaches the

open backdoor of All Hallows (St. Andrew's Roman Catholic

Church). He steps into the porch and doffs his hat:

5.322.

Same notice on the door. Sermon by the very reverend John Conmee

5.323. S. J. on saint Peter

Claver S. J. and the African Mission. Prayers for the

5.324. conversion of

Gladstone they had too when he was almost unconscious.

5.325. The protestants are

the same. Convert Dr William J. Walsh D. D. to the

5.326. true religion.

Save

China's millions. Wonder how they explain it to the

5.327. heathen Chinee.

Prefer

an ounce of opium. Celestials. Rank heresy for

5.328. them. Buddha

their god

lying on his side in the museum. Taking it easy with

5.329. hand under his

cheek.

Josssticks burning. Not like Ecce Homo. Crown of

5.330. thorns and

cross.

Clever idea Saint Patrick the shamrock. Chopsticks?

(Underlining mine.)

In the

Roman Catholic church, Bloom remembers and mocks the Jesuit

missionaries in China showing his sympathy for the Chinese

people. Bloom's comment on gheathenh Chinese people's preference

for an ounce of opium over Christianity might satirize the Opium War

between Britain and Ching Dynasty China (1839-42). Then he

remembers the reclining Buddha statue he saw in the National Museum of

Ireland in Kildare Street. The Buddha statue, from Burma, is very

beautiful,

well-proportioned and, sensual, when compared with gstately and

plumph Buddha statues in East Asia. The Buddha statue was

presented in 1891 by Colonel Sir Charles Fitzgerald as ga trophy of

Britain's newest colony exhibited to the people of her oldesth

according to John Smurthwaite (3).

[photo

unavailable]

gThe figure is of marble, with the drapery painted gold, and is

140 cm long by 23 cm wide by 41 cm highh (Smurthwaite 3).

Bloom mistakenly associates the

Buddha's reclining pose with idleness, gtaking it easy with his hand

under his cheekh (U

5.328-29). In fact, the reclining Buddha

statue was made to express how the Buddha attained the Nirvana after he

had eaten a pork dish offered by Cunda, the smith, which made his

stomach totally incurable: ghe had bedding spread with the head towards

the north according to the ancient custom. He lay upon it, and

with his mind perfectly clear, gave his final instructions to his

disciples and bade them farewellh according to Olcott (22). So

Bloomfs association can be read as a parody because his sleeping pose

is later described to look like the reclining Buddha by Molly (U

18.1199-202).

The

episode name, gLotus-Eaters,h brings to mind the Buddha, because the

Buddha is typically portrayed sitting on a lotus flower that arises

pure from the muck. Joyce probably knew the lotus flower is also

the important symbol for the Buddha. In Mahayana Buddhism, one of

the most important and influential sutras is the gLotus Sutra.h

In the Odyssey, the Lotus

Eaters appear in Book IX. Early in

Odysseus's voyage he and his men were driven by a storm to the land of

the Lotus-Eaters, ga race that live on vegetarian foodh and Odysseus

disembarked to take on water. Some of Odysseus's men met the

friendly Lotus-Eaters, and ate the lotus: gAll they now wished

for was to stay where they were with the Lotus-eaters, to browse on the

lotus, and to forget that they had a home to return

toh(141).12 Odysseus drove

the infected men back

to the

ships and set sail. Bloom here regards Ceylon as a land of the

Lotus-Eaters and longs for the reclining Buddha, contrasting its

peaceful image with Christ's torture of thorns and cross. After

the church service ends, Bloom goes out and walks southward along

Westland Row to Sweny's (a chemist). He buys a sweet lemony wax

for Molly. Then he walks cheerfully towards the mosque-shaped

Turkish baths. The episode ends with glotus flower,h a metaphor

for the fulfillment of his name gBloomh and his nom de plume gHenry

Flowerh: gHe foresaw his pale body reclined in it at full, naked, in a

womb of warmth, oiled by scented melting soap, softly laved. He

saw... his navel, bud of flesh: and saw the dark tangled curls of his

bush floating, floating hair of the stream around the limp father of

thousands, a languid floating flowerh (U

5.567-72). It is a

Joycean association of the Buddha/bud/bod (Ir. penis) often found in

Finnegans Wake. Here

Bloom becomes a reclining Buddha in his

mind.

In gScylla

and Charybdis,h Stephen Dedalus mocks and parodies Theosophy and

Buddhism (U 9.65-70; 279-85).

Stephen, while discussing Hamlet

based on

his analysis of Shakespearefs biography, performs a monologue on

contemporary Irish writersf interests in Oriental thoughts including

W.B. Yeats, George Russell and James Stephenfs. Stephen's comment

on the Buddha is, as he monologues, probably influenced by Mme

Blavatsky's Isis Unveiled.13

In gOxen of the Sun,h

Stephen cites

the Theosophists' works about the karmic law and re-incarnation:

gTheosophos told me so, Stephen answered, whom in a previous existence

Egyptian priests initiated into the mysteries of karmic lawh (U

14.1168-69).

Needless to say, the two concepts

of re-incarnation and the karma are also Buddhist terms.

Molly

thinks in gPenelopeh:

18.1199. hes sleeping at the

foot of the bed how can he without a hard bolster its well

18.1200. he doesnt kick or he

might knock out all my teeth breathing with his hand

18.1201. on his nose like

that Indian god he took me to show one wet Sunday in the

18.1202. museum in Kildare

street all yellow in a pinafore lying on his side on his

18.1203. hand with his ten

toes sticking out that he said was a bigger religion than

18.1204. the jews and Our

Lords both put together all over Asia imitating him as hes

18.1205. always imitating

everybody I suppose he used to sleep at the foot of the bed

18.1206. too with his big

square feet up in his wifes mouth damn this stinking thing

In Molly's imagination, Bloom's

sleeping pose is similar to that of the Buddha's statue. Bloom,

now impotent after his son Rudy's death, has not had sexual intercourse

with Molly for a long time. The Buddha never had sex after

leaving his wife Yasodhara and his child at the age of 29.

Bloom's sleeping pose identifies him with the reclining Buddha.

Molly's comment reminds the readers of Bloom's obscure longing for the

Far East he shows in gLotus Eaters.h

Then when did

Joyce think of putting these Buddhist references into Ulysses? In

Ulysses's Notesheet, the word

gBuddhah appears twice: gR <A Gautama,

A Jesus, An Ingersoll>h (gCirceh II, 324; U 15.2198-9), gR <LB

Buddha> (gPenelopeh I; U

18.1199-205). In gScylla and

Charybdis,h Stephen's Buddhist references in the two passages can be

seen in the Rosenbach Manuscript (9,2&8) and the Little Review

version (V, 11,32&37) with some theosophical terms like gIsis

Unveiled,h gPali bookh and gmahamahatmah: Joyce added some more

theosophical terms including glife esoteric,h gkarma,h and goversoulh

to the same passages later at the stage of Typescript (Buffalo

V.B.7;JJA 12.351;354).

The last Buddhist reference Joyce inserted

is in gLotus Episodeh at the stage of Placard X: gBuddha their god

lying on his side in the museum. Taking it easy with hand under

his cheek. Not like Ecce Homo. Crown of thorns and crossh

(JJA 17.190;U 5.328-30). Judging from the

dates Joyce inserted

the Buddhist references, he planned to use them in Ulysses from the

beginning. So it is rather surprising Joyce inserted the

reclining Buddha passage last, while Molly's mentioning the Buddha

statue was planned earlier. However, Joyce seems to have decided

in which part of the novel to introduce the statue after long

deliberation.

Conclusion

Bloomfs ambivalence about the Orient is rooted

in his ambiguous gAsianh background. As we have seen, Bloom

thinks of the Orient as an Orientalist who escapes from the reality and

fantasizes of being in some Oriental place. However, he also

notices: gProbably not a bit like it really. Kind of stuff you

read: in the track of the sunh (U

4.99-100).

Carol Loeb Shloss argues, gFor Joyce, Irish

dreams of the Orient and the Irish need for dreaming them were a

measure of a perceived human dangerh (Shloss 270). As we have

seen, Irish Orientalism has two dimensions. Irish people

sometimes have despised and exploited the Orient in the same way as

British and French people have. They have also felt a sympathy

for the Orientals with a vague fraternity. Irish Orientalists in

Joycefs time were often the nationalists who needed to differentiate

Irish culture from Anglicized culture.

gCeltic Tiger,h a name for the rapid economic

growth in the Republic of Ireland in the 1990s, was a legacy of Irish

Orientalism adoring the East Asian tigers such as those of China and

South Korea which achieved great economic growth in the 1980s and

1990s. Irish-Oriental connections no longer hold academic

credibility. However, Irish Orientalists including Joyce used

some Oriental motifs and elements in their works as a literary device

or as a mode of modernism to express their complex cultural identity.

As we have seen, Joycefs Orientalism

began in Dublin, influenced by Theosophy and Buddhism/Hinduism as well

as Judaism. His inclination toward the Orient was much

intensified and expanded in the Oriental mood of Trieste. In the

late 1930s in Paris, when Joyce struggled to complete Finnegans Wake,

his Orientalism finally reached East Asia in the last chapter, Book IV,

which is full of Asian elements.

Notes

**This research is granted Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C)

(No. 18520223) by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science under the title of gJames Joyce and

Orientalism.h

1. Cf. gWikipedia: eOrientalism (Book).fh

2. On June 27, 2002, Ito was allowed to see multiple statues of the reclining Buddha in

the depository of National Museum of Ireland \ Decorative Arts & History at Collins

Barracks. As of September 2008, the museum has approximately 30 Buddhas according

to Audrey Whitty, curator of ceramics, glass & Asian collections of the museum. As she

tells, gApprox. eight Buddha statues were given on loan in 1891 by Col. Charles Fitzgerald.

Some were returned in the early 20th century to his family, but about 4/5 remain here in

the museumh (e-mail to Ito dated on 15 September, 2008).

3. Cf. Said's Orientalism: "For Orientalism was ultimately a political vision of reality

whose structure promoted the difference between the familiar (Europe, the

West, 'us') and the strange (the Orient, the East, 'them')" (43). Cf. also

McCourt, p.42.

4. To describe his imagination on the dark Jewish lady, Joyce constellated many

Eastern elements in Giacomo Joyce: "A ricefield near Vercelli" (GJ 2), "A sparrow

under the wheels of Juggernaut" (GJ 7), "the breaking East" (GJ 9), etc.

5. See Itofs article gfUnited States of Asiaf: James Joyce and Japan,h 199-203.

6. Cf. gWikipedia: eHungary.fh

7. An Israeli writer fabricated a visit by Joyce to Palestine between March 23 and April

2, 1920 (Nadel 4). In September 1940, the Swiss Eidgenossiche Fremdenpolizei

[Federal Aliensf Police] refused Joyce and his family permission to enter the country

on the grounds that they were Jewish (JJ 736-37). These two anecdotes suggest

how successfully Joyce described Jews in Ulysses.

8. See U 8.1162, 10.1268, 13.1166, 15.1494 and 15.4109.

9. Cf. Don Gifford, gUlyssesh Annotated, p.283. The opening of the Mirus Bazaar was

not on 16 June but on 31 May 1904. There was no cavalcade that day, although

the viceroy actually attended the opening ceremony (283). This bazaar was held in

splendid weather and successfully ran until 4 June. The total attendance was

54,565 and the hospital received 4,399 3s 4d (Lyons 147).

10. The programme was full of the local advertisements. The most attractive entertainment

was Englandfs premier comedian/pianist James Stewart, gThe Tramp at the Piano,h who

was featured in pp.6-7. No Oriental name is found in the gList of Artists.h

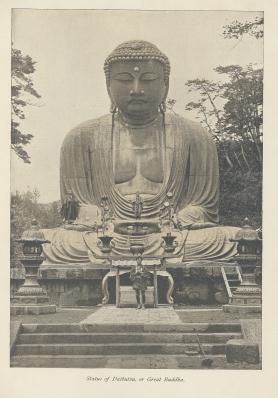

11. In gKIOTO AND ITS TEMPLESh of Chapter IV. gFAREWELL TO JAPAN,h the same

photo appears again and the writer comments: gAfter dinner I visited a Japanese theatre,

and saw some curious dancing. The dancers, wearing very rich and handsome dresses,

kept time, in slow and graceful movements, to the music of flutes, guitars, and small

drums, played by twelve Japanese girlsh (55). The verso of the title page is the gstately

and plumph gStatue of Daibutsu, or Great Buddhah which is probably the Great Buddha

of Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan:

12. Homer, the Odyssey (trans. E. V. Rieu), p. 141.

13. See Itofs article gMediterranean Joyce Meditates on Buddha,h pp.59-60.

References

James Clarence Mangan.h James Joyce Quarterly, Vol.35, no.2/3 (Winter/Spring

1998), 309-31.

Ellmann, Richard. James Joyce. New and Revised ed. Oxford and New York,etc.:

Oxford University Press, 1982.

Gifford, Don and Robert J. Seidman. gUlyssesh Annotated: Notes for James Joycefs

gUlysses.h 2nd ed. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press,

1988.

Greek-English Lexicon, A (9 Rev Sub). Eds. Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Homer. The Odyssey. Trans. E. V Rieu. London: Penguin Books, 1946.

gHungaryh: From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia:

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hungary> Accessed: September 6, 2008.

Ito, Eishiro. "Mediterranean Joyce Meditates on Buddha." Language and Culture,

No.5. Center for Language and Culture Education and Research, Iwate Prefectural

University, January 2003, 53-64.

---. gfUnited States of Asiaf: James Joyce and Japan.h A Companion to James Joyce.

Ed. Richard Brown. Malden, Ma, Oxford and Carlton, Victoria: Blackwell

Publishing, 2008.

Joyce, James. The Critical Writings of James Joyce. Eds. Ellsworth Mason and Richard

Ellmann. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989.

---. Giacomo Joyce. With an Introduction and Notes by Richard Ellmann. London and

Boston: Faber and Faber, 1968; pap.1983. Referred to as GJ.

---. The James Joyce Archive. 63 vols. Eds. Michael Groden, etc. New York &

London; Garland Publishing, 1978.

---. Joyce's gUlyssesh Notesheets in the British Museum. Ed. Phillip F. Herring.

Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1972.

---. Ulysses. Ed. Hans Walter Gabler. London: The Bodley Head, 1986. Referred

to as U x.y (x= the episode number, y = the line number in each episode).

---. Ulysses: A Facsimile of the Manuscript. London: Faber and Faber Ltd. in

association with The Philip H. & A. S. W. Rosenbach Foundation, Philadelphia,

1975.

Lennon, Joseph. Irish Orientalism: A Literary and Intellectual History. Syracuse,

NY: Syracuse University Press, 2004.

Lyons, J. B. James Joyce & Medicine. Dublin: The Dolmen Press, 1973.

McCourt, John. The Years of Bloom: James Joyce in Trieste 1904-1920. Dublin: The

Lilliput Press, 2000.

gMirus Bazaar, Ballfs Bridge, Dublin, 1904: The Advertisersf Guyed and Cafe Chantant

Programme.h Printed by John T. Drought, 6 Bachelorfs Walk, Dublin.

Molnár, Miklós. A Concise History of Hungary. Trans. Anna Magyar. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Nadel, Ira B. Joyce and the Jews: Culture and Texts. Iowa City: University of Iowa

Press, 1989.

Olcott, Henry S. The Buddhist Catechism. London: Theosophical Society, 1903.

gOrientalism (book)h: From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia:

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientalism_(book)> Accessed: September 2, 2008. <

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

Shloss, Carol Loeb. gJoyce in the Context of Irish Orientalism.h James Joyce

Quarterly, Vol.35, o.2/3 (Winter/Spring 1998), 264-71.

Smurthwaite, John. gThat Indian God.h James Joyce Broadsheet, 61 (Feb.2002),

3.

Thomfs Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for the

Year 1904. Dublin: Alex. Thom & Co., 1904.

Thompson, Frederick Diodati. In the Track of the Sun: Reading from the Diary of a

Globe Trotter. London: William Heinemann. 1893.