Introduction

This paper aims to

focus on Diaspora Jews in

James Joyce's Ulysses. The

Diaspora group embodied a powerful

economic principle and became a great threat to the local Irish people,

that

caused anti-Semitic movements. Joyce

precisely reflected on this mood, but sometimes tactically manipulated

it in

his fictional world.

Leopold

Bloom is known among his acquaintances to have a Hungarian Jewish

background

and have inherited a financial competence from his suicidal father.

However, he and his wife Molly, who has a

suspicious Jewish mother, are not orthodox Jews, so they are isolated

from

other members of the Jewish community.

In the novel, other Jewish people and anti-Semites are often

observed. How did Irish Jewish people

live in Dublin? How does Ulysses reflect the

truth? Using some historical and socioeconomic data,

Irish Jewish lives in the Jewish quarter called "Little Jerusalem," and

other parts of Joycean Dublin will be examined.

I. The Jewish "Invasion" of Ireland

In 1866, the year of Bloomfs

birth, the Jewish population

of Dublin numbered about two hundred and that of Belfast at most a few

dozen,

before the Litvak ginvasionh beginning in the late 1870s.

Dublinfs Jewish quarter near Bloomfs

fictional birthplace at 52, Clanbrassil Street Upper was called gLittle

Jerusalem.h By 1904, the estimate

was 3,371, most of them (2,200) residing in Dublin, according to Leon

Hühnerfs gJews

of Ireland.h The transition in numbers of

the Jewish population was more remarkable than that of London,

Manchester and

Liverpool before the foundation of Israel in 1948.

As Cormac Ó

Gráda argues in Jewish Ireland in the Age of Joyce, in

economic terms, Irelandfs Jewish community made considerable

progress between the 1870s and the 1940s, because in Ireland,

discrimination

did not force the immigrants into typical Jewish jobs, like peddling,

money-lending and dealing in scrap and rags and in secondhand furniture

(Ó

Gráda 210).

Jewish people had already acquired trading skills.

In addition, the immigrants saved and

invested in property, education, and business (Ó Gráda 210-11). Irelandfs

relative economic backwardness shaped both the number and the choice of

occupations of the Jewish immigrants at that time.

No one could have imagined the future gCeltic

Tigerh then.

As some examples of the

negative reactions against the Jewish ginvasion,h many anti-Semitics

are

described in Ulysses. The fictional Garret

Deasy tells Stephen that gIreland,

they say, has the honour of being the only country

which never persecuted the jews,h gBecause she never let them inh (U 2.437-47). In

gLestrygonians,h Bloom watches the notoriously

anti-Semitic judge Sir Frederick Falkiner

(1831-1908), going into the Freemason Hall (headquarters) in 17-18,

Molesworth

Street (U 8.1151). In the mood of

anti-Semitism of Barney Kiernanfs pub in gCyclops,h Bloom faces the

anti-Semitic gcitizenh who is modeled after Michael Cusack (1847-1907), a Gaelic

athletic enthusiast who

founded the Gaelic Athletic Association in 1884. In

the pub, Bloom is also rumored to give the

ideas for Sinn Fein to Arthur Griffith (1872-1922) who became the first

president of the newly formed Irish Free State in 1922 (U

12.1573-77) and was also known as a notorious anti-Semite.

II. Dublin's "Little Jerusalem"

The first

known record of Jews living in Dublin dates to the late seventeenth

and early eighteenth centuries, probably Jews displaced following the

expulsions from the Iberian Peninsula according to Educational

Jewish Aspects of James Joyce's "Ulysses" (or

EJAJJU

4).

The earliest known synagogue dates back to

1660 and was situated in Crane Lane.1 The

Napoleonic Wars brought a further influx

of Jews to Dublin, records of the births and deaths were kept by a Rev.

J.

Sandheim, minister of Stafford Street and Maryfs Abbey synagogues

(1820-1879) (EJAJJU 4).

It

was in the late nineteenth century that a new wave of immigrants

reached

Ireland, many of whom were fleeing Anti-Semitism which was encapsulated

by the

May Laws in the Pale of Settlement, Russia from 1881. These

people came from Lithuania, Latvia,

Russia, Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe. They settled

all over Ireland, but the largest

community settled in the South Circular Road area of Dublin. This

area, where the synagogues and Jewish

business came into being, was gradually known to non-Jews as gLittle

Jerusalemh

(EJAJJU 4).

As

Ó Gráda notes, virtually all of Irelandfs

Jewish immigrants settled in urban areas as other Jewish immigrants did

in

other European countries in the late nineteenth century.

On the eve of World War I nearly nine in ten

lived in one of the three major cities: Dublin, Belfast, or Cork. There were also small settlements in Limerick

(119), Waterford (62), Derry (38), and most surprisingly in the Armagh

linen

town of Lurgan (about 75) (Ó Gráda 94).

Naturally, they became

traders and skilled

artisans who apparently have earned much more money than average Irish

workers. In Dublin, the newcomers tended

to live in

the tenements in central Dublin, near Dublin Castle, or Maryfs Abbey

where the

cityfs only synagogue functioned until 1892.

Ó Gráda

estimates that the Lithuanian

Jewish population numbered about twenty-five in the late 1870s (Ó Gráda

97). They did not remain in the tenements

so long,

but they moved to the complex of small streets off Clanbrassil Street

Lower in

the early 1880s. As Nick

Harris remembers in

Dublinfs Little Jerusalem, Clanbrassil

Street was the heart of the Jewish community (Harris 30).

It catered to all the Jewish people in

Dublin, and, in the early twentieth century, for at least 95 percent of

them it

was within walking distance (Harris 30).

Clanbrassil Street is located south of St. Patrick Cathedral in

the

Southside of Dublin. As often discussed,

Bloom lives at a tenement of No. 7 Eccles Street in the Northside of

Dublin

across the River Liffey. The area was

traditionally considered as being more working-class, although

Clanbrassil

Street area then, and also today, is not for the rich.

However, the average valuation of the

tenements of the eighty houses of Eccles Street rated

for each municipal tax per annum was about 31.33 while that of the seventy-eight houses

of Lombard Street West was 15.21 and

the twenty-five houses of St. Kevinfs Parade 14.52 as calculated the assessed values

listed in Thomfs Official Directory 1904.2 From the assessed values of the houses,

gLittle

Jerusalemh was much more working-class than Eccles Street.

According

to research by Ó Gráda, the housing stock, mainly roadside one-story

terraced

units, was new or almost new. Most units

contained outside flush toilets and running water: dwellings

incorporating

three or four small rooms were typical.

The area that would soon come to be known as gLittle Jerusalemh

included

most of the streets between Saint Kevinfs Parade and the Grand Canal.

At the turn of the century, there were two

small clusters with very heavy concentrations of Jews: one around Saint

Kevinfs

Parade/Oakfield Place/Lombard Street West, and the other across the

South

Circular Road, around Kingsland Parade/Walworth Road/ Martin Street by

the

Grand Canal (Ó Gráda 99). There was a

hierarchy of streets within the ghetto and the Jews sharply sensed

class

distinctions. Although the majority of Jews

lived in gLittle Jerusalem,h the area was not exclusively Jewish, with

a number

of Gentile neighbors.

Joyce very

cautiously selected Bloomfs

fictional birthplace at 52,

Clanbrassil

Street Upper and his old address in Lombard Street West in gLittle

Jerusalem.h The Blooms lived in the Jewish quarter until

they left presumably in mid-1894, when Bloom was twenty eight and Molly

was

twenty three after they lost their only son Rudy (U 8.608-10).

15.3220. earth. The passing bell is heard. Darkshawled figures of the

15.3221. circumcised, in sackcloth and ashes, stand by the wailing wall, M.

15.3222. Shulomowitz, Joseph Goldwater, Moses Herzog, Harris

15.3223. Rosenberg, M. Moisel, J. Citron, Minnie Watchman, P. Mastiansky,

15.3224. the reverend Leopold Abramovitz, chazen. With swaying arms they

15.3225. wail in pneuma over the recreant Bloom.) (Underlining mine.)

It

is to be noted that the above people were real Jewish people.

According to Educational

Jewish Aspects of James Joycefs gUlysses,h most grealh

Jewish figures described in the novel lived in gLittle Jerusalemh:

The

list of the Jews of gLittle Jerusalemh described in Ulysses3:

Leopold Abramovits, Chazen (reader), according to Hyman is the same person as

Abraham Lipman Abramovits, Reader of the Lennox Street Synagogue. He came

to Dublin in 1887 and served the community as a ritual slaughterer, Mohel

(circumciser) and Hebrew teacher (EJAJJU 9).

2. Bloom, Joseph: 3, Blackpitts.5

3. Bloom, Leopold: 52, Clanbrassil Street Upper (15).6 A plaque in front reads;

gHere, in Joycefs imagination, was born Leopold Bloom, citizen, husband, father,

worker, the reincarnation of Ulysses.h An elderly dapper Bennie Bloom

(1881-1966) is sometimes mentioned as a model for his Joycean namesake (Ó Gráda

60). On 16 June 1904 he and his wife Molly lives in a tenement at 7, Eccles Street.

According to Thomfs 1904, the house is gVacant, [valuation of the tenement rated

for its municipal tax per annum:] 28.h

4. Blum, Isaac: 3, Desmond Street (17).7 (?U 15.721-22 [von Blum Pasha],

?U 17.1748 [Blum Pasha])

5. Citron, Israel: 28, St. Kevinfs Parade.8 (U 4.204-06, 7.219-20, 8.178,

15.1904-7; with Mastiansky, ?U 15.3223 [J.Citron], 15.4357, 18.573). J. Citron

(a misprint for I. Citron) has been identified by Hyman as Israel Citron (1876-1951),

a peddler who lived at 17, Kevinfs Parade between 1904 and 1908 (Ó Gráda 106).

It is also significant that his name was chosen by Joyce because the citron fruit,

used in the feast of Tabernacles, is symbolic of all the wandering tribes of Israel

and of the coming redemption that will reunite all the tribes (EJAJJU 8; Cf. Hyman

168).

6. Goldwater, Joseph: 77, Lombard Street W. (16). (U 15.3222). gHere the Dublin

Hebrew Young Menfs Association met. Their officials in 1899 were I.M. Shmulowitz,

Isaac Shein, M. Citron, H. Greentuch & Solomon Bloom. Joseph Goldwater lived at

77, Lombard Street West. It was at this address that the Dublin Hebrew Young

Menfs Association met at the end of the nineteenth centuryh (EJAJJU 8-9).

7. Herzog, Moses: 13, St. Kevinfs Parade (13).9 (U 12.17 & 33; U 15.3222 &

4357-58). Moses Herzog, according to Hyman, was a one-eyed bachelor and

bibulous peddler who emigrated to South Africa in 1908 (Hyman 329). He lived at

13, St. Kevinfs Parade between 1894 and 1906, near to Citron and Mastiansky, and

traded as an itinerant grocer (EJAJJU 9; Cf. Hyman 168; Ó Gráda 106). Herzog

was also an unlicensed moneylender (Ó Gráda 64) who is described so in the beginning

of gCyclops.h

8. Masliansky [Mastiansky, Philip or Julius]: 16, St. Kevinfs Parade (16).10 (U 4.205,

6.770, 15.1904-7; with Citron, U 15.3223, 4357, 17.58 [Julius (Juda) Mastiansky],

U 17.2134 [Julius Mastiansky], U 18.417 [Mrs.Mastiansky]). O. Mastiansky may be

a misprint for P. Mastiansky (U 15.3223), the same person as Julius Mastiansky, who

figures in Ulysses as one of Molly Bloomfs lovers (U 17.55-59). The name Masliansky

appears in the Midwifefs register which was the account book of Nurse Shillman who

was working in Dublin at the turn of the century (EJAJJU 8). According to the

entries of Masliansky, two children were born to Philip Masliansky and Florrie Leause

in 1899 & 1901 (EJAJJU 8).

9. Moisel, Wolf: 24, St. Kevinfs Road (14).11 (U 4.209, ?8.391-92 [Mrs.

Moisel], ?U 15.3223 [M.Moisel]. U 17.1254 [Philip Moisel (pyemia, Heytesbury

Street)]). M. Moisel is probably one and the same as Nisan Mosel, ritual

slaughterer and Mohel to the Jewish Community in Dublin. Nisan Moisel was the

father of Elyah Wolf Moisel (1856-1904), whose wife Basseh gave birth to a

Daughter Rebecca in June 1889, thirteen days after Molly Bloomfs daughter Milly

was born (U 8.391-92).12 The name Moisel was originally spelt Moiselle (EJAJJU

9). Bloomfs father Rudolf Virag changed his Hungarian family name to its

anglicized form, Bloom. Name-changing was very common among the members of

the Jewish community, usually for ease of spelling or pronunciation.13

10. Rosenberg, H. [Harris]: 63, Lombard Street W. (16).14 (U 15.3222-23). Little

is known of Harris Rosenberg other than he lived at 63, Lombard Street West.

However, among the entries of nurse Shillmanfs register is an entry for the birth

of a daughter to a Mrs. H. Rosenberg in 1907 (EJAJJU 9).

11. Shulomowitz (Shmulovich), M.: 57, Lombard Street W. (U 15.3221-22). M.

Shulomowitz is probably M. Shmulovitch (d. 1940) who was the secretary of the

Jewish Library, 57, Lombard Street West (23).15 He was the Dublin correspondent

of the London Hebrew Weekly, Hayehudi, who emigrated to South Africa in 1904,

returning some years later and settling in Cork, where he married the daughter of Rev.

Elyan, Minister of the Cork Hebrew Congregation (Hyman 328).

12. Watchman, Minnie: 20, St. Kevinfs Parade (15). (U 15.3223). Minnie Watchman

was the great-aunt of the author Louis Hyman who lived at 20, St. Kevinfs Parade.

The inclusion of her name in the list of the circumcised may be a private joke on

the part of Joyce due to her appearance in Thomfs 1905 [also in Thomfs 1904] with

the prefix Mr. before her name (EJAJJU 9).

The above

people all lived

in gLittle Jerusalemh around 1904. The

majority of them still lived in tenements:

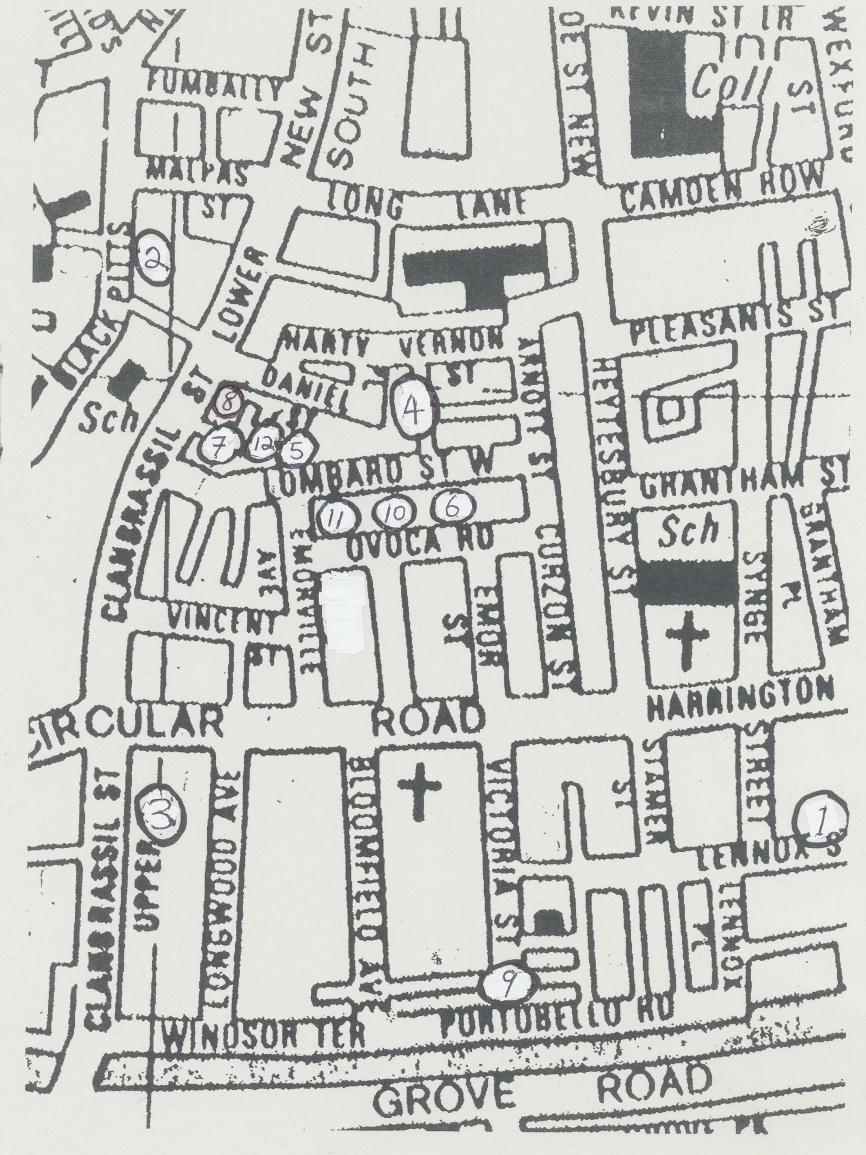

Map

of Dublinfs gLittle

Jerusalemh (Adapted from Educational

Jewish Aspects of James Joycefs gUlysses,h 5)

It

is ironic that Leopold Bloom is the only

fictional Jewish character in the above list of the residents of

gLittle

Jerusalem.h In fact, there was a Mollie

Bloom, who married a Human Wachman, living at 28, Hammond Street,

Blackpitts (EJAJJU 8).16 However, his family name gBloomh

(or Blum) itself was a common Jewish name, not only in Dublin but also

in other

European cities.

Bloom often remembers his childhood friends Citron and Mastiansky,

which

makes him seen like a real Jew living in gLittle Jerusalem.h

[Israel] gpoor

Citronh & Mastiansky:

4.202. olivetrees. Quiet long days: pruning, ripening. Olives are packed in jars,

4.203. eh? I have a few left from Andrews. Molly spitting them out. Knows the

4.204. taste of them now. Oranges in tissue paper packed in crates. Citrons too.

4.205. Wonder is poor Citron still in Saint Kevin's parade. And Mastiansky with

4.206. the old cither. Pleasant evenings we had then. Molly in Citron's

4.207. basketchair. Nice to hold, cool waxen fruit, hold in the hand, lift it to the

4.208. nostrils and smell the perfume. Like that, heavy, sweet, wild perfume.

4.209. Always the same, year after year. They fetched high prices too, Moisel told

4.210. me. Arbutus place: Pleasants street: pleasant old times. Must be without a

4.211. flaw, he said. Coming all that way: Spain, Gibraltar, Mediterranean, the

4.212. Levant. Crates lined up on the quayside at Jaffa, chap ticking them off in a

4.213. book, navvies handling them barefoot in soiled dungarees. (Underlining mine.)

"Poor"

In another

description in the hallucination of gCirce,h both Mastiansky

and Citron are described with stereotyped Jewish features. They wear gabardines

and long earlocks like Jewish people in the Middle Ages.

They approach their friend Bloom wagging

their beards.

Mastiansky,

Citron and Reuben J. Dodd (English moneylender described as a Jew):

15.1897. HORNBLOWER

15.1898. (in ephod and huntingcap, announces) And he shall carry the sins of the

15.1899. people to Azazel, the spirit which is in the wilderness, and to Lilith, the

15.1900. nighthag. And they shall stone him and defile him, yea, all from Agendath

15.1901. Netaim and from Mizraim, the land of Ham.

15.1902. (All the people cast soft pantomime stones at Bloom. Many bonafide

15.1903. travellers and ownerless dogs come near him and defile him.

15.1904. Mastiansky and Citron approach in gaberdines, wearing long

15.1905. earlocks. They wag their beards at Bloom.)

15.1906. MASTIANSKY AND CITRON

15.1907. Belial! Laemlein of Istria, the false Messiah! Abulafia! Recant!

15.1908. (George R Mesias, Bloom's tailor, appears, a tailor's goose under

15.1909. his arm, presenting a bill)

15.1910. MESIAS

15.1911. To alteration one pair trousers eleven shillings.

15.1912. BLOOM

15.1913. (rubs his hands cheerfully) Just like old times. Poor Bloom!

15.1918. (Reuben J Dodd, blackbearded Iscariot, bad shepherd, bearing on

15.1919. his shoulders the drowned corpse of his son, approaches the

15.1920. pillory.)

15.1921. REUBEN J

15.1922. (whispers hoarsely) The squeak is out. A split is gone for the flatties. Nip

15.1923. the first rattler. (Underlining mine.)

George Robert Mesias was also a real Jew in Dublin.

Mesias, Bloomfs tailor (see U 6.831, 11.881,

15.1302, 15.1908-11,

17.2171) of 5 Eden Quay, was a native of Russia and appears in a parade

of

false messiahs in gCirce.h In the Census

of Ireland, 1901, he is listed as a widower of the Jewish persuasion,

aged 36,

lodging at the home of Hoseas Weiner in Clontarf West.

A tall and handsome man, he married Elsie

Watson as his second wife, on 5 November 1901 at Clontarf Presbyterian

Church

(Hyman 168).

Reuben J. Dodd is a moneylender, and the passengers all curse

him when

the funeral carriage passes him by in gHadesh because they all except

Bloom have

owed money to Dodd (U 6.251). The real Reuben J. Dodd mercilessly collected money from

Joycefs

father John Stanislaus Joyce when he almost became bankrupt (Davison

58-59). The reader may

believe Bloom's thought that

Reuben J. Dodd was "really what they call a dirty jew" (U

8.1159), but the real Dodds were not

Jewish but English in origin. However,

in the biography of Joyce's father, John

Stanislaus Joyce, by John Wyse Jackson and Peter Costello the view

is that

Joyce's father, John Stanislaus, fabricated Dodd's Jewishness, blaming

him in

revenge for his financial disasters (Jackson & Costello 179).

There are many Jewish figures living in other places in Dublin,

such as Dr

Hy Franks, an English Jew appearing in Ulysses

(U 15.2633), a "quack" [fraudulent]

doctor who had posters stuck up in greenhouses and urinals offering

treatment

for venereal diseases. gAll kinds of

places are good for adsh (U 8.95-96)

is Bloomfs observation on Franksf promotional activities.

In gCirce,h Lipoti Virag, Bloomfs

grandfather, transforms into a bird butting with its head the fly bill

for

advertising the pox doctor, and cries, eQuackf

(U 15.2627-38). Henry

Jacob Franks, born in Manchester in

1852, arrived in Dublin in 1903 after deserting his Turkish-born wife

Miriam (U 8.350 [Miriam Dandrade], 9.449, 15.2994-3000, 15.4360-61 [Mrs

Miriam Dandrade] ;née Mandil) and their

four children (Hyman 168).

Maurice E. Solomons (U

10.1262), an optician, was a prominent member of Dublinfs Jewish

community. His business is listed as being

at 19, Nassau

Street, Dublin as goptician, manufacturer of spectacles, mathematical

&

hearing instruments, 56h and also

as gThe Austro-Hungarian Vice-Consulate\Imperial and Royal

Vice-Consul, Maurice E. Solomons, J.P.h (Thomfs

1904).

He was appointed to the job by

Archduke Ferdinand.17

The

derogative name for Jews gIkey Mosesh (U

9.607, etc), the fictional butcher Moses Dlugacz (U 4, U 11 & U 15) and the fictional Bloom

the

dentist (U 12.1638) are also

described in the novel, while Bella Cohen, who appears as the madam of

the

brothel in gCirce,h was probably modeled on "Mrs. Cohen" at 82,

Mecklenburg Street in the heart of Dublin's then 'red light' district

(Hyman

168).18

III. Jewish Economic "Threats"

and Limerick "Pogrom"

Throughout the eighteenth century, Sephardi bankers were

prominent in

England and remained so even when, in the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries,

the Frankfurt-based Rothchilds provided loans to the British government

for the Crimean and Boer Wars and

the building of the Suez Canal (Feinstein 42). As often mentioned in many occasions,

moneylending is the most stereotyped Jewish job.

In

the previous chapter, Reuben J. Dodd, actually an English moneylender,

is

described as a Jew by Bloom: "Now hefs really what they call a dirty

jew" (U 8.1159). This

anecdote also indicates the common sense

among the Irish that moneylenders and usurers are typical Jewish jobs

which

were despised by Gentiles. In gScylla

& Charybdis,h Stephen Dedalus presents his theory on Shakespeare

saying, gHe

drew Shylock out of his own long pocketh (U

9.741-42). John Eglinton urges Stephen

to prove that Shakespeare is a Jew (U

7.763). Everyone enjoys Stephenfs

unconvincing

argument in the National Library.

The higher economic status of moneylenders is apparent from a

list of

Jewish moneylenders prepared by the Dublin police in 1905 (Ó

Gráda 61). Some moneylenders doubled as merchants.

No Jewish moneylendersf ledgers have been unearthed, and it

seems

unlikely that any will be uncovered (Ó Gráda 63). Many loans were transacted

without any formal

paperwork (Ó Gráda 64).

The

poor who needed to replenish stock relied on moneylenders who knew them

to help

them. Unlicensed moneylenders like

Joycefs Moses Herzog could not pursue defaulters through the courts

(cf. U 12.13-51).19

Moses Herzog is

mentioned as an unlicensed moneylender:

12.13. --Devil a much, says I. There's a bloody big foxy thief beyond by the

12.14. garrison church at the corner of Chicken lane - old Troy was just giving

12.15. me a wrinkle about him - lifted any God's quantity of tea and sugar to pay

12.16. three bob a week said he had a farm in the county Down off a

12.17. hop-of-my-thumb by the name of Moses Herzog over there near

12.18. Heytesbury street.

12.19. --Circumcised? says Joe.

12.20. --Ay, says I. A bit off the top. An old plumber named Geraghty. I'm

12.21. hanging on to his taw now for the past fortnight and I can't get a penny out

12.22. of him.

12.23. --That the lay you're on now? says Joe.

12.24. --Ay, says I. How are the mighty fallen! Collector of bad and doubtful

12.25. debts. But that's the most notorious bloody robber you'd meet in a day's

12.26. walk and the face on him all pockmarks would hold a shower of rain. Tell

12.27. him, says he, I dare him, says he, and I doubledare him to send you round

12.28. here again or if he does, says he, I'll have him summonsed up before the

12.29. court, so I will, for trading without a licence. And he after stuffing himself

12.30. till he's fit to burst. Jesus, I had to laugh at the little jewy getting his shirt

12.31. out. He drink me my teas. He eat me my sugars. Because he no pay me my

12.32. moneys?

12.33. For nonperishable goods bought of Moses Herzog, of 13 Saint

12.34. Kevin's parade in the city of Dublin, Wood quay ward, merchant,

12.35. hereinafter called the vendor, and sold and delivered to Michael E.

12.36. Geraghty, esquire, of 29 Arbour hill in the city of Dublin, Arran quay ward,

12.37. gentleman, hereinafter called the purchaser, videlicet, five pounds

12.38. avoirdupois of first choice tea at three shillings and no pence per pound

12.39. avoirdupois and three stone avoirdupois of sugar, crushed crystal, at

12.40. threepence per pound avoirdupois, the said purchaser debtor to the said

12.41. vendor of one pound five shillings and sixpence sterling for value received

12.42. which amount shall be paid by said purchaser to said vendor in weekly

12.43. instalments every seven calendar days of three shillings and no pence

12.44. sterling: and the said nonperishable goods shall not be pawned or pledged

12.45. or sold or otherwise alienated by the said purchaser but shall be and remain

12.46. and be held to be the sole and exclusive property of the said vendor to be

12.47. disposed of at his good will and pleasure until the said amount shall have

12.48. been duly paid by the said purchaser to the said vendor in the manner

12.49. herein set forth as this day hereby agreed between the said vendor, his heirs,

12.50. successors, trustees and assigns of the one part and the said purchaser, his

12.51. heirs, successors, trustees and assigns of the other part. (Underlining mine.)

Moses

Herzog's, 13, St. Kevin's Parade, South Circular Road,

The

one-eyed moneylender Herzog was mocked by

the I-narrator of gCyclopsh who imitates his broken English. This suggests that Herzog was an immigrant

Jew. In the late nineteenth century,

moneylending was a sensitive issue for the Jewish community in both

Britain and

Ireland.20

Anti-Semitism actually existed in Ireland, although it was less

severe

than that in other European countries.

It reached its climax in Limerick in early 1904, when a young

Redemptorist preacher, Father John Creagh (1870-1947), who had lived in

France at

the height of the Dreyfus Affair, led to the boycott that prompted the

departure of several households in the cityfs small Jewish community. At the time, Limerick was a city of about

forty thousand people. Poverty was ripe;

in the 1890s and 1900s one Limerick family in ten still lived in a

one-room

tenement (Ó Gráda 191).

Jews in Limerick, like those in other Irish cities, were mainly

middlemen traders. Apart from two gdental

mechanicsh and two clergymen, all male household heads and boarders

listed in

the 1901 census were described as peddlers, drapers, or shopkeepers. Most of the community lived in small houses

on Colooney (now Wolfe Tone) Street, half a mile or so west of the city

center (Ó

Gráda 191). One household

in two could

afford a live-in domestic servant in 1901, a sign that Litvak Jewry by

then had

achieved a modicum of comfort and respectability (Ó

Gráda 191).

The events in Limerick are often regarded as the most serious

outbreak

of anti-Semitism in recent Irish history (Ó Gráda 192). Creaghfs sermons led to a

boycott against the

cityfs Jewish traders. This not only

prohibited new business; it also led to opportunistic defaulting on

outstanding

debts. Creagh omitted to mention that

Limerickfs most prominent moneylenders were Gentiles.

In the wake of Creaghfs sermons some Jews

were physically assaulted and their property threatened (Ó

Gráda 192). In the

following months several

households in the one hundred and seventy member community left the

city. The decline from one hundred and

seventy in

1901 to one hundred and nineteen a decade later was not entirely due to

the

boycott, although the boycott was still in force in 1905 (Ó

Gráda 192).21

The

Limerick incident is ambiguously implied in "Penelope" in Ulysses: "he [Arthur Griffith] knew there was a

boycott" (U 18.387). This

may refer to the threatened boycott

against Jews in Limerick and a press-boycott involving Griffith's paper

United Irishman in 1904, although the

context also suggests a boycott related to the two Boer Wars.

Also, there are

some other references possibly conveying the anti-Semitic mood in

Ireland at

that time. In the

graveyard scene in

Glasnevin Cemetery in gHades,h Bloom remembers Mastianskyfs reference

to opium,

then associates the blood sinking into the earth and remembers someone

saying

that those Jews killing the Christian boy is based on the same idea of

perversion of fertility:

Mastiansky

& LBfs reference to the Jewish blood libel:

6.769. flowers of sleep. Chinese cemeteries with giant poppies growing produce the

6.770. best opium Mastiansky told me. The Botanic Gardens are just over there.

6.771. It's the blood sinking in the earth gives new life. Same idea those jews they

6.772. said killed the christian boy. Every man his price. Well preserved fat corpse,

6.773. gentleman, epicure, invaluable for fruit garden. A bargain. By carcass of

6.774. William Wilkinson, auditor and accountant, lately deceased, three pounds

6.775. thirteen and six. With thanks. (Underlining mine.)

It

is

significant that Bloom just describes the superstitious anti-Semitic

legend

without comment. Later, in Bloomfs

apartment and in the presence of Bloom, Stephen sings the anti-Semitic

ballad

of gLittle Harry Hughes and the Dukefs Daughter [Jewfs Daughter]h in

which a

Jewish girl cuts off the head of a Christian boy (U 17.810-28).22 Bloom,

unsmiling and with mixed feelings,

hears the song and silently tries to find gthe possible

evidences for and against ritual murderh (U 17.844-49).

Bloom is not a Jew in

strict terms and he gintermarriesh

a Catholic woman Molly. As Ó Gráda

argues, Irish Jewry avoided assimilation through intermarriage (Ó Gráda

213). Bloom moved to a tenement of 7,

Eccles Street in North Dublin and lives with his family as a non-Jewish

or gassimilatedh

Jew apart from the Jewish community.

Bloomfs financial status is comparatively high, although he does

not own

a home yet. On June 16, 1904, he

received a commission of 1 7s 6d, evidently selling

an advertisement (U 7.113), which is precisely one and

two-thirds of Stephen Dedalusfs

weekly earnings.23 In total,

Bloom possesses almost 1500 in assets (Osteen 92).

Joyce realistically renders Jewish stereotypes by portraying Bloom and

his Jewish forebears as examples of every type of perceived economic

threat,

from immigrant ragman and hawker to assimilated merchant and financier

(Feistein 41).

Conclusion

Having

selected an gassimilatedh Jewish couple as the novelfs central

characters with

numerous detailed descriptions of real Jewish Dubliners, Joycefs Ulysses left a historical record of how

Jews and Gentiles regarded each other in early twentieth-century

Ireland. Rosemary Horan mentions that gJames

Joyce once stated that if Dublin were

destroyed, it could be reconstructed from the text of Ulysses. It is our

[Irish-Jewish peoplefs] hope that in some way we can reconstruct the

essence of

Jewish Dublin of 1904h (EJAJJU 4). This is a convincing comment of the accuracy

with which Joyce described Irish Jewish peoplefs lives in Ulysses.

Now, not so many Dubliners recognize the

former Jewish quarter gLittle Jerusalem.h

The number of Irish Jews has remarkably declined and most Dublin

Jews moved

to the southern suburbs of Dublin in the mid-twentieth century. However, the Irish Jewish Museum was opened on

the site of Walworth Road Synagogue (which ceased to function in the

mid-1970s)

by the Irish-born 6th President of Israel Dr. Chaim Herzog (1918-1997;

p.1983-1993) on 20th June 1985. Together

with the museum, Joycefs Ulysses

greatly evoked Gentile peoplefs attention to Irish Jews.

Joyce had many good gassimilatedh Jewish friends throughout his

life. He definitely knew the tremendous

effect of employing a nowhere cosmopolitans or wandering Jew belonging

to ga

nation without a countryh as the protagonist of his Dublin-setting

novel. With the Jewish protagonist and

other Jewish

elements Ulysses gained a

cosmopolitan status in world literature.

Notes

*This is a

revised version of the paper presented at IASIL 2007, University

College Dublin, Ireland, July 17, 2007.

**This research is granted Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (No. 18520223)

by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science under the title of gJames Joyce and

Orientalism.h

1. Cf. EJAJJU 4: "Further evidence of an early date is the fact that Ballybough

Cemetery in Fairview, just north of Dublin, was in use from the early 18th century

onwards."

2. St. Maryfs Private Hospital, 38, Eccles Street, is not included for the calculation

because no valuation

was shown in the entry.

3. Main reference: EJAJJU 4.

4. According to the gList of the Nobility, Gentry, Merchants, and Traders, Public

Officers, &c., &c.h of Thomfs 1904, he is noted: gAbramovitz, Rev. Leopold,

Jewish minister, 3 Kevinfs road.h

5. 3, Blackpitts was not recorded in Thomfs 1904, probably because Blackpitts were full

of small cottages for artisans.

6. According to Thom's 1904, the house was occupied by Mr. E. Tucker.

7. According to Thom's 1904, the house was occupied by Mr. T. Freedman and Mrs.

S. Bloom.

8. Thom's 1904 only records houses from no.1 to no. 25 of St. Kevin's Parade, and it

notes, "17 Citron, Mr. J. 16l. [16]." However, as Joyce purposely (?) used the wrong

house number in the text of Ulysses (U 7.219-20), Citron is supposed to have lived in

28, St. Kevin's Parade in Joyce's fictional world.

9. His name is recorded as "Herzog, Mr. M." in Thom's 1904.

10. As Hyman notes, Philip Masliansky lived at 2, Martin Street in 1896, and at 63,

Lombard Street West in 1899-1900, and from 1900 to 1906 at 16, St. Kevin's

Parade (Hyman 189). Thom's Directories record him as Phinis (sic) Mosliansky in 1899

and 1900, as P. Masliansky in 1901 and as P. Mastiansky in 1902-1906 (Hyman 189).

11. According to Thom's 1904, the house was occupied by Mr. Alexander Mitafsky.

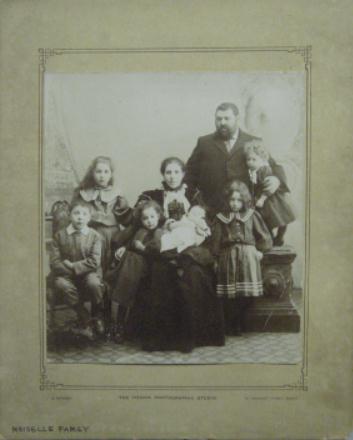

12. The Irish Jewish Museum is in possession of a photograph of the Moisel family,

which features the daughter Rebecca:

(Courtesy

of the Irish Jewish Museum)*

13. A good example of such a change was the name Good. Judge Herman Good was

the son of the Rev. Gudansky. The name Bloom may originally have been Blum,

Roseblum, etc. (EJAJJU 9).

14. Cf. Thom's 1904.

15. Cf. Thom's 1904.

16. Cf. Thom's 1904. Hammond Street, Blackpits had 55 small cottages (4 15s to 6)

for artisans. Probably he lived at one of them.

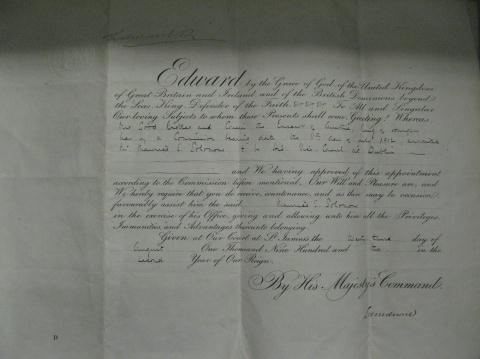

17. The original documents of this appointment, bearing the seal of Ferdinand, are in

the possession of the Irish Jewish Museum (EJAJJU 9):

(Courtesy

of the Irish Jewish Museum)*

19. Cf. Ó Gráda, 64-66: The nature of the unlicensed money lendersf operations almost

certainly entailed higher interest charges. They operated outside the law in an

equilibrium involving higher costs, higher interest charges, smaller loans, and higher

default rates. Most Jewish moneylenders lived within the law, however, and relied

on the courts to enforce their contracts. They did not resort to the violent tactics

used by some illegal operators (Ó Gráda 66).

20. In 1898, when legislative controls on moneylending were imminent, Sir George Lewis

testified to a parliamentary inquiry (Ó Gráda 66):

I know that the Jewish community despise and loathe these men and their trade;

they are not allowed any public position in the community; they are utterly ignored;

the Jewish clergy preach against them and their usury in the synagogues; and I may

say this because I know it of my own knowledge. I am myself a Jew. (Ó Gráda 66)

Lewis continued with remarks that reflected the hostility of many in his own

anglicized community to its immigrant coreligionists (Ó Gráda 66):

It is impossible that the community can do anything with these men, who come over

from Poland, Jerusalem and other places, and start themselves up on this way, but

they would be only glad to see them to put down and abolished altogether, and

imprisoned. (Ó Gráda 66)

21. The Catholic bishop of Limerick, Dr. Edward OfDwyer (1842-1917), was criticized

both at the time and later for not condemning Creagh and the boycott publicly. In

private, OfDwyer tried to intervene, but he had little ecclesiastical authority over

Creagh. Moreover, he had little sympathy for the local Jewish community (Ó

Gráda 193).

22. Cf. Don Gifford,gUlyssesh Annotated, 579. Gifford refers to English and Scottish

Popular Ballads (eds. Francis James Child and George Lyman Kittredge, Cambridge,

1904). The ballad gLittle Harry Hughes and the Dukefs Daughterh is a variant of

gSir Hugh; or, the Jewfs Daughterh (No. 155). As Gifford notes, its substitutes

gDukefs Daughterh for gJewfs Daughterh in genteel avoidance of the balladfs

ganti-Semitism.h The original story from which the ballad derives is of a boy, High

of Lincoln, supposedly crucified by Jews in c.1255 (Gifford 579).

23. Cf. Osteen, 92. Bloom has a 500 life insurance policy, a savings account of

18-14-6, and 900 worth of the Canadian government stock at 4 percent, free of

stamp duty (U 17.1856-65). His stock earns him 6 per year.

References

Child, Francis James and George Lyman Kittredge, eds. English and Scottish Popular

Ballads: Studentfs Cambridge Edition. Boston, New York, etc: Houghton Mifflin

Company, 1904.

Davison, R. Neil. James Joyce, gUlysses,h and the Construction of Jewish Identity:

Culture, Biography, and gThe Jewh in Modernist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1996.

Ellmann, Richard. James Joyce. New and Revised ed. Oxford and New York,etc.:

Oxford University Press, 1982.

Feinstein, Amy. gUsurers and Usurpers: Race, Nation, and the Performance of Jewish

Mercantilism in Ulysses.h James Joyce Quarterly, 44.1 (Fall 2006), 39-58.

Fishberg, Maurice. The Jews: A Study of Race and Environment. London: The Walter

Scott Publishing Co., Ltd., 1911.

Gibson, Andrew. Joycefs Revenge: History, Politics, and Aesthetics in gUlysses.h

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Gifford, Don and Robert J. Seidman. gUlyssesh Annotated: Notes for James Joycefs

gUlysses.h 2nd ed. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press,

1988.

Harris, Nick. Dublinfs Little Jerusalem. Dublin: A. & A. Farmar, 2002.

Hühner, Leon. "The Jews of Ireland: An Historical Sketch." Transactions of the Jewish

Historical Society of England, 5 (1902-5), 226-42.

Hyman, Louis. The Jews of Ireland from Earliest Times to the Year 1910.

Shannon: Irish University Press, 1972.

Irish Jewish Museum, The. Educational Jewish Aspects of James Joycefs gUlysses.h

Dublin: The Irish Jewish Museum, 1992.

Jackson, John Wyse and Peter Costello. John Stanislaus Joyce: The Voluminous Life

and Genius of James Joycefs Father. London: Fourth Estate, 1997.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Ed. Hans Walter Gabler. London: The Bodley Head, 1986.

Referred to as U x.y (x= the episode number, y = the line number in each episode).

Magalaner, Marvin. gThe Anti-Semitic Limerick Incidents and Joycefs gBloomsday,h

PMLA, LXVIII (1953), 1219-23.

McCarthy, Patrick A. gThe Case of Reuben J. Dodd.h James Joyce Quarterly, 21.2

(Winter 1984), 169-75.

Nadel, Ira B. Joyce and the Jews: Culture and Texts. Iowa City: University of Iowa

Press, 1989.

Ó Gráda, Cormac. Jewish Ireland in the Age of Joyce: A Socioeconomic History.

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Osteen, Marc. The Economy of gUlyssesh: Making Both Ends Meet. New York:

Syracuse University Press, 1995.

Reizbaum, Marilyn. James Joycefs Judaic Other. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press, 1999.

---.gThe Jewish Connection, Contfd.h The Seventh of Joyce. Benstock, Bernard, ed.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979, 229-37.

Steinberg, Erwin R. gThe Source(s) of Joycefs Anti-Semitism in Ulysses.h Ed. Thomas

F. Staley. Joyce Studies Annual 1999. Austin: University of Texas, 1999.

Thomfs Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for the

Year 1904. Dublin: Alex. Thom & Co., 1904.

*I am indebted to Curator Raphael V. Siev of the Irish Jewish Museum for granting permission to reproduce the photograph of the Moisel family and take a photo of the document of Maurice E. Solomonsf appointment to use for this article.