A

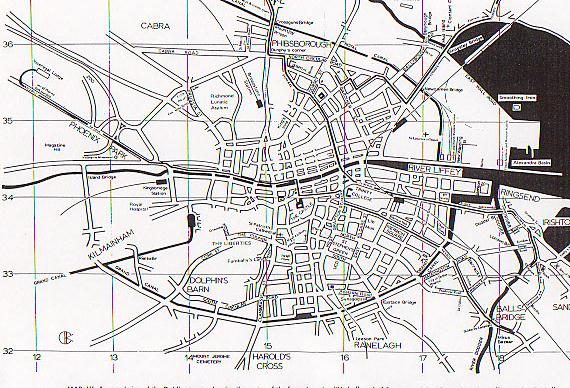

general view of the Dublin streets, showing the route of the funeral cortege,

etc.9

"I am the insurrection and the life":

Reading Irish Nationalism in the 6th Episode of Ulysses

Eishiro Ito (1999)

|

James

Joyce's Ulysses is said to be based on a very fine detailed city

map of 1904 Dublin. In fact, Joyce himself told Frank Budgen that

if Dublin was destroyed, it would be possible to rebuild it by looking

at this novel. In Ulysses Paddy Dignam died of a heart attack

three days before the Bloomsday, June 16 1904. In the 6th episode

"Hades," Bloom, with three other mourners, travels on the funeral carriage

from Dignam's house near Sandymount Strand in the southside of Dublin to

the Glasnevin Cemetery in the northside. The carriage moves

throughsome major streets of Dublin including Sackville Street. Bloom (or

the narrator) conveys what the four of them see through the window during

the trip carefully and constantly while they keep on talking about one

thing or another. But when the carriage passes Sackville Street,

Bloom's attention curiously misses the famous General Post Office (or GPO)

along the crowded street. Why does he intentionally ignore the GPO

and Sackville Street? At the funeral, Bloom (or the narrator)

is haunted by a necrophiliac obsession and narrates the physical grotesqueness

of decay in death very minutely. Why does he continue to imagine

the anatomical reality of death so pathologically? Surveying

Joyce's manuscripts of this episode, we are surprised at how many dark

phrases were inserted after the first publication of this episode in The

Little Review, September 1918. Joyce wrote Ulysses between

1914 and 1922 when Ireland faced the most bloody and severe time of its

history: World War I, the Easter Rising 1916, the Anglo- Irish War and

the Irish Civil War occurred during this time. The GPO and Sackville

Street became the center of the Easter Rising and were damaged.

There were many Irish nationalists buried in the Glasnevin Cemetery

The cemetery itself is a symbol for Irish Catholics, who were liberated

by Daniel O'Connell in 1831 since Irish Catholics could not conduct a full

Catholic funeral service under Protestant control before that time.

|

|

(Policy Studies Association, Iwate Prefectural University, December 1999), 437-452. Copyright 1999 Eishiro Ito

|

Introduction

James Joyce's

Ulysses is said to be based on a very fine detailed

city plan of 1904 Dublin. In fact, Joyce himself told Frank Budgen

that if Dublin was destroyed, it would be possible to rebuild by referring

to this novel.1 Actually, we can easily trace the way

the characters move about in the novel because Dublin in general has not

changed radically in spite of the series of Irish wars and other historical

events that happened between 1904 and today.

Ulysses consists of

18 episodes, each of which has a name based on Homer's Odyssey. Many

critics and scholars have already pointed out that Joyce carefully depicted

the streets, the shops and people by looking at Thom's Directory

1904 and various books on historical events in Dublin and the map of Dublin

within his own memory. Especially in the 4th to 6th episodes, we

can imagine what streets were like in Dublin in Joyce's time. In

the 5th episode Bloom took his time and wandered on purpose from his house

to the public bath near Trinity College. The episode ends with the

scene of Bloom's taking a bath. But on the opening of the 6th episode

Bloom was about to ride on the carriage for the Dignam's funeral in New

Bridge Avenue near Sandymount Strand. Then the mythic journey to

the Glasnevin Cemetery (or Prospect Cemetery), in other words, the journey

to Hades, starts.

As Stuart

Gilbert introduces one of Joyce's schemata, this episode is as in Table

1 2;

and Richard Ellmann

transcribes the correspondences to the Odyssey in Table 2 3

:

| Table 1. | GORMAN-GILBERT SCHEMA | Table 2. | MYTHICAL CORRESPONDENCES |

| SCENE | The Graveyard | Sisyphus | Martin Cunningham |

| HOUR | 11 a.m. | Cerberus(guard dog) | Father Coffey |

| ORGAN | Heart | Hades the god | John O'Connell |

| ART | Religion | Hercules | Daniel O'Connell |

| COLOURS | White: Black | Elpenor | Paddy Dignam |

| SYMBOLS | Caretaker | Agamemnon | John Stewart Parnell |

| TECHNIC | Incubism | Ajax | John Henry Menton |

In the simplest sense, the focus is on the graveyard scene. The setting time of the episode of death is curiously correspondent to that of the 14th episode of birth, "Oxen of the Sun."4 The "Heart" is referred to in many ways: 1)Dignam's heart-breakdown caused by his heavy drinking(U06.305), 2)Sacred Heart(U06.954), etc.. The color of "White: Black" definitely expresses the funeral or mourning for the dead. The well-known caretaker John O'Connell personifies Hades himself: "All the mourners make a point of speaking well of the caretaker--an echo of the Euripidean eulogy of Hades and such euphemism as the designation of the Eumenides, la veuve for the guillotine and so forth."5 The technic "Incubism" is difficult to analyze: Mark Osteen explains in The Economy of "Ulysses" that the word "incubism" is derived from the Latin incubo (nightmare), inferring that Stephen's nightmare of history encompasses Bloom's episodes, just as Stephen is haunted by memories of the dead6:

...In

one sense, "incubism" connotes the dead's oppression of the living,

the

kind of psychic incubi seen in such Dubliners stories as "The Dead."

But

the word from which incubo stems, incubare (to lie upon), also connotes

birth,

because from this root comes the word incubation and its connotations

of

warmth, nurturing, and birth. Lying upon eggs hatches them:

incubism

becomes

incubation; both ends meet. As in the number eleven, and as in

Bloom's

conversation of Rudy's death into the moment of his conception, the

same

sign may signify both death and birth.

(100)

In this essay, I"d like to discuss the significance of vividly depicting

the streets of Dublin and the Glasnevin Cemetery in this episode.

I. The Route to Glasnevin

The first

half of the "Hades" episode reprises the characters and enclosed space

of the sickroom scene in "Grace" of Dubliners: Martin Cunningham, Jack

Power, Bloom and Simon Dedalus ride together in one funeral carriage while

Tom Kernan rides in another. Stephen Dedalus and Blazes Boylan are

glimpsed along the route(U06.39&199).7 The

model of Paddy Dignam is Mr Matthew Kane, chief clerk of the Crown Solicitor

Office in Dublin, who suffered a stroke when he swam off Kingstown Harbour,

10 July 1904. Three days later his body was borne in a cortege from

Kingstown to Glasnevin. Like Dignam, he had five children and an

alcoholic wife who surprisingly did not attend her husband's funeral.Joyce

and his father were among the mourners.8

To

begin with, we trace the route Bloom and his companions take in the carriage.

Joyce carefully selected the route because it is believed that there are

four rivers in Hades(Styx, Acheron, Cocytus and Pyriphlegethon), so the

carriage must pass through four rivers (the Dodder, the Grand Canal, the

Liffey and the Royal Canal) for the mythical correspondence. In this

episode there are quite numerous reflections of Bloom's, about life/sex

and death. The opening scene is set outside Paddy Dignam's home,

No.9 Newbridge Avenue, Sandymount. Bloom is the last to get into

the carriage, so we can assume that his seat is on the left side, considering

the location of Dignam's, the direction of travel and the Irish social

customs at that time. He sees an old woman peeping at them through

a window, and dwells for a moment on the role of women in life/sex and

death, bringing us into the world and tending our corpses at the end, thinking

of his wife Molly and his housekeeper Mrs Fleming. The carriage moves

off and the trip to the Glasnevin Cemetery begins.

A

general view of the Dublin streets, showing the route of the funeral cortege,

etc.9

Pedestrians take off their hats as the funeral procession goes by. Bloom, a mythical father, sees Stephen Dedalus clad in mourning, a mythical son, walking down Irish Town Road(U06.39-40). Bloom recalls his own son Rudy, who died soon after he was born, and wishes he were alive. Then the carriage goes along Ringsend Road, and passes Wallace Bros the bottleworks and Dodder Bridge, across the first of the four rivers. Bloom recollects the actual morning of Rudy's begetting, Molly's self-reproduction in Milly, with her maturing interest in a "young student" [Alec Bannon] as revealed in that morning's letter to "Dearest Papli." After talking about Corny Kelleher and Charley M'Coy, the carriage halts suddenly at the second bridge across the Grand Canal when they look out Gasworks whose smell is said to cure whooping cough and dwells on the diseases of children. The sight of the "Dogs' home" reminds Bloom of his dead father, whose last wish was that Leopold should be good to his old dog Athos. The dog isn't living anymore, and does not correspond to Cerberus which is a guardian dog of Hades with 3 heads and a snake-like tail. Rather, Athos corresponds to Argus, the dog owned and trained by Odysseus before he engaged in the service according to the Odyssey. Argus in his owner's absence, lay abandoned on the heaps of dung from the mules which lay in profusion at the gate, awaiting removal by Odysseus's servants as manure for his great estate. But directly after he became aware of Odysseus's presence, he wagged his tail and dropped his ears, though he lacked enough strength now to come nearer to his master.10 The absence of Athos is very meaningful, because this means that there is no one who can prove that Bloom is a mythical father. The third bridge is doubtlessly O'Connell Bridge across the Liffey, the most famous and biggest river in Dublin, but it is never described in this episode. The carriage goes through Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street), the busiest and biggest street in Dublin, but there's no admirable description of it. Joyce tactically described the route they go: the Red Bank (U06.198) is Burton Bindon's restaurant, 19-20 D'Olier Street and Smith O'Brien's statue(U06.226) made by Thomas Farrell (U06.228), which stands at the intersection of Westmoreland Street and D'Olier Street where they converge at O'Connell Bridge.11 It is around 11 a.m. Thursday when many people walk up and down Sackville Street, but Bloom (or the narrator) never expresses how busy this street is and does not mention the famous General Post Office(GPO) which can be seen from the window on his side. The only things and people he refers to are two statues of the Irish heroes, Liberator Daniel O'Connell and Thomas Gray, which must be on the opposite side of Bloom, and Reuben J. Dodd, Jewish solicitor, who bent on a stick, stumping round the courner of Elvery's Elephant house.12 Moreover, he describes the street like this:

Dead side of the street this. Dull business by day, land agents,

temperance

hotel, Falconer's railway guide, civil service college, Gill's,

catholic

club, the industrious blind. Why? Some reason. Sun or wind. At

night

too. Chummies and slaveys. Under the patronage of the late Father

Mathew.

Foundation stone for Parnell. Breakdown. Heart.

White horses with white frontlet plumes came round the Rotunda

corner,

galloping. A tiny coffin flashed by. In a hurry to bury. A mourning

coach.

Unmarried. Black for the married. Piebald for bachelors. Dun for a

nun.

(U06.316-24)

Needless

to say, Sackville Street was the main and most important street of Dublin.

At noon Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, 1,558 volunteers led by Patrick Pearse

and an estimated 219 of the Irish Citizen Army led by James Connoly occupied

the GPO in the middle of Sackville Street and proclaimed the Irish Republic

there. Then the GPO became the rebel headquarters until they surrendered

on 1 May. Sixty-four republicans died in action. Of the 20,000

British troops involved in the fighting during the week, 103 were killed

and 357 wounded. Between 3-12 May, fifteen Irish patriots were executed.13

Crowds

viewing damage to the GPO, Easter 191614

With

the speciously justifiable reason of dealing with the 1904 Dublin, Joyce

never described the GPO and the lively view of Sackville Street here: he

only depicted some major streets of Dublin as a necropolis, "another world

after death named hell" (U06.1001-2). As seen in my Introduction,

Joyce told Frank Budgen: "I want," said Joyce, as they were walking down

the Universitatstrasse, "to give a picture of Dublin so complete that if

the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed

out of my book."15> This conversation took

place "one Sunday afternoon during the winter of 1931-2" (preface),

when Joyce already knew what happened around the GPO in Sackville Street

in 1916. So it seems to me that Joyce purposely did not describe

the GPO and the vigorous view of Sackville Street in this episode, partly

because the setting of the next episode "Aeolus" is the Freeman's Journal

Office, behind the GPO in Prince's Street North.

The

carriage climbs more slowly the hill of Rutland Square: "Rattle his bones.

Over the stones. Only a pauper. Nobody knows" (U06.332-33).

Then Martin Cunningham said, "In the midst of life" (U06.374) which

of course reminds us of the opening passage of Dante's Inferno: "Nel mezzo

del cammin di nostra vita." The most plausible source of this aphorism

is, however, included in "The Burial Service" in the book of Common Prayer

by the Church of England according to Don Gifford.16 The

carriage rattles swiftly through Blessington Street, Berkeley Street near

the City Basin, in front of the Mater Misericodiae Hospital along Eccles

Street near Bloom's house. Then it gallops round the corner and suddenly

stops again because of a divided drove of branded cattle passing.

Bloom complains about the bad condition of Dublin traffic, and the occupants

begin to talk about the hearse capsizing round Dunphy's pub and upsetting

the coffin on to the road. So Bloom imagines a case in which Dignam's

coffin might suffer from the same thing(U06.421-26). It is

the beginning of his vivid imagination about the Catholic dead who, different

from the Protestant, were buried into the ground uncremated as a religious

custom. In silence they drive along Phibsborough Road and pass Crossguns

Bridge: the Royal Canal, the last river. Then soon they pass Brian

Boroimhe house, steer left for Finglas Road and arrive at the Prospect

Cemetery in Glasnevin.

II.

At the Glasnevin Cemetery

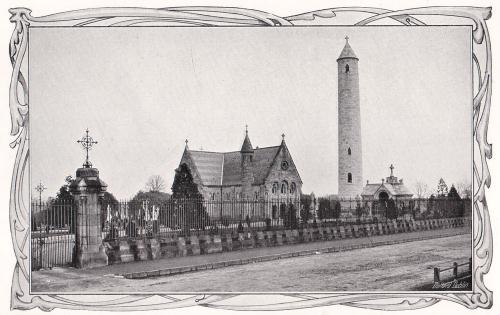

Part

View Entrance to Glasnevin Cemetery17

Before

discussing each description at the cemetery, we need to know the history

of the cemetery itself. According to Glasnevin Cemetery:

An Historic Walk(or GCHW) in the sixth century, the saint Mobhi is believed

to have established a seat of learning in Glasnevin on the banks of River

Tolka, and both Saint Columba and Saint Canice were reputed to have studied

under him(5).18 After the Norman invasion in the twelfth

century, the church and lands of Glasnevin became the property of the Prior

of the Holy Trinity (Christchurch). However, by the 18th century,

Glasnevin's saintly status had obviously diminished somewhat, and now with

the Phoenix Park and with the nearby Botanic Gardens, the Glasnevin Cemetery

forms part of the Green Belt around Dublin(5). Prior to the establishment

of the Glasnevin Cemetery, Irish Catholics had no cemeteries of their own

in which to bury their dead and as the repressive Penal Laws placed heavy

restrictions on the public performance of Catholic services, it had become

normal practice for Catholics to conduct a limited version of their own

funeral services in Protestant cemeteries. Alternatively, a sod of

clay might be placed in the coffin before it was removed from the place

of mourning and the funeral rites conducted there instead(5).

The public outcry helped Daniel O'Connell launch a campaign and prepare

a legal opinion to show that no law could prohibit the Catholic burial

service in cemeteries under Protestant control.19 He knew

that it was very difficult to conduct a full funeral service in what was

intended to be a strictly Protestant cemetery and that Catholics needed

burial grounds of their own: the "Act of Easement of Burial Bills" was

passed in 1824.20 The new ground at Glasnevin was blessed

on 29th September 1831, and a Michael Carey became the first person to

be interred on February 21st, 1832.21 The ground was enclosed

on 29th April 1833 and by 1878, 295,081 burials had taken place.

Today, the original site of nine acres has grown to one of more than 120

acres, making it the largest cemetery in Ireland, according to GCHW(6).

As we have seen, the Glasnevin Cemetery is an important memorial place

for Dublin Catholics. So many Irish nationalists were buried here,

including Daniel O'Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell, Michael Cusack, John

O'Leary, James Stephens, Roger Casement, Michael Collins, etc.

They reach the cemetery. Bloom comments it is a "paltry funeral"

(U06.498) with one coach and three carriages. Mourners, including

John Henry Menton who once danced with Molly, come out, but Mrs Dignam

and four of his five children do not come here: only his eldest son Patrick

and his uncle Bernard Colligan(Paddy's brother-in-law) come to Glasnevin

to attend the funeral. The mutes, or grave-diggers come in and shoulder

the coffin and bear it in through the gates. The mourners follow.

Corny Kelleher, who works for Henry J. O'Neill, carriage maker and undertaker,

arranges various things for the funeral. Father Coffey begins to

read out of his book, but wears the mask of Cerberus, and his name is like

a coffin, Bloom thinks (U06.595-600). The mourners move again.

They pass the memorial circle of Daniel O'Connell, liberator of this cemetery

to the Catholic. Simon Dedalus points to his wife's grave, breaks

down and weeps silently(U06.645-51).22 On the way

to the cemetery, Bloom feels pain for his son's death, the adultery between

his wife Molly and Blazes Boylan, and his father's suicide, but here in

the cemetery, he is unaffected by the dead, although he pretends to show

sympathy for the dead before the other mourners. Rather, he sarcastically

imagines the anatomical reality of death:

Mr Kernan said with solemnity:

---I

am the resurrection and the life. That touches a man's inmost heart.

---It

does, Mr Bloom said.

Your heart perhaps but what price the fellow in the six feet by two

with

his toes to the daisies? No touching that. Seat of the affections. Broken

heart.

A pump after all, pumping thousands of gallons of blood every day.

One

fine day it gets bunged up: and there you are. Lots of them lying

around

here: lungs, hearts, livers. Old rusty pumps: damn the thing else.

The

resurrection and the life. Once you are dead you are dead. That last

day

idea. Knocking them all up out of their graves. Come forth, Lazarus!

And

he came fifth and lost the job. Get up! Last day! Then every fellow

mousing

around for his liver and his lights and the rest of his traps. Find

damn

all of himself that morning. Pennyweight of powder in a skull.

Twelve

grammes one pennyweight. Troy measure. (U06.669-81)

Different

from Protestants' custom, Catholics have been burying the dead uncremated

into the ground, because the Holy Office in May 1886 opposed cremation

and the code of Canon Law promulgated in 1919 continued to oppose it, though

today all Christian denominations allow cremation.23

There are three watchtowers in the cemetery, one placed at the south boundary

to the botanic garden, the others along Finglas Road: they were built to

defend the cemetery from the incursions of bodysnatchers, as it is reported

in GCHW(27). Throughout the story of Irish medical anatomical education,

there are numerous references to the difficulties of obtaining bodies for

anatomical dissection. If there was no one to bury them, the bodies

of executed criminals were sometimes provided for dissection (indeed, it

was quite common for men sentenced to death to sell their bodies to the

surgeons beforehand, generally so that they might spend the proceeds on

alcohol), but despite this practice, there never seemed to have been enough

to satisfy eager medical students. "Sack-'em-Ups" or "Resurrectionists"

were professional bodysnatchers hired by the medical profession to obtain

bodies for them(27). This scene contains many dubious and suggestive

descriptions about the rotting corpses in the ground, which might allude

to the bodysnatchers. Caretaker John O'Connell's following story

is one of them:

---They

tell the story, he said, that two drunks came out here one foggy

evening

to look for the grave of a friend of theirs. They asked for Mulcahy

from

the Coombe and were told where he was buried. After traipsing about

in

the fog they found the grave sure enough. One of the drunks spelt out the

name:

Terence Mulcahy. The other drunk was blinking up at a statue of

Our

Saviour the widow had got put up.

The caretaker blinked up at one of the sepulchres they passed. He

resumed:

---And,

after blinking up at the sacred figure, Not a bloody bit like the man,

says

he. That's not Mulcahy, says he, whoever done it. (U06.722-31)

Sometimes the Sack'-em-Up men burrowed at an angle towards the coffin so

that the earth immediately over it was undisturbed when the mourners examined

it the next morning. Occasionally, the body would be dragged from

its coffin, dressed up and carried away, disguised as a drunken man staggering

home between two friends according to GCHW (27-28). Various techniques

were used to remove the body from the coffin. The attempts had to

be made as soon as possible after interment so that the earth had not completely

settled and was reasonably easy to remove. Occasionally it was possible

to expose an end of the coffin, break it open, tie a rope around the neck

or ankles and drag the body out --- this was easier if the coffin in question

was a pauper's coffin, which were made of the cheapest and thinnest timber(27).

So it could be easier if someone tries to snatch poor Dignam's body from

his cheap coffin. Martin Cunningham apologies for Kelleher's

story, saying "That's all done with a purpose. To cheer a fellow

up. It's pure good heartedness: damn thing else" and Joseph Hynes

agrees with him(U06.735-38). It might be the author's satire

about the bodysnatchers, for Joyce, who once had an ambition to become

a medical student, doubtlessly knew it. Bloom's obsession of the

physical grotesqueness of decay in death continues on and on. It

may be quite natural for Bloom to imagine the above quotation, because

he is a Jewish Irish and was a Protestant before he converted to Catholicism

in order to marry Molly: he satirizes like this because he is apparently

isolated or alienated, at least since he boarded the carriage this morning:

he was the last one to get on and get off, and nobody felt it strange.

Probably such things often happen in his daily life. And here in

the Catholic cemetery, he feels more alienation among many Catholic mourners.

The mourners take up their positions around the grave, and Bloom notices

a mysterious stranger in a macintosh: "Now who is that lankylooking galoot

over there in the macintosh? Now who is he I' like to know?" (U06.805-6).

He counts the mourners around the grave: "Twelve. I'm thirteen.

No. The chap in the macintosh is thirteen. Death's number"

(U06.824-26). The grave-diggers put the coffin down into the

grave, and the mourners pray for the repose of Dignam's soul. Then

the diggers take up their spades and fling heavy clods of clay on the coffin.

Hynes, a journalist of the Evening Telegraph, writing down the names

of the mourners, checks Bloom's Christian name. Bloom stresses "L,"

with odd irony in view of the fact that when the printed list of the mourners

appears in the newspaper, the letter "L" is deleted from his surname "Boom"

(U16.1248-61). Bloom faithfully asks for Charley M'Coy's name

to be added to the list.24 When Hynes questions if Bloom

knows "that fellow in the, fellow was over there in the ..." he answers

"Macintosh." Then Hynes misunderstands Macintosh as his name, so

Bloom tries to correct his misunderstanding in vain when he moves away.

M'Intosh, the unidentifiable figure, will appear in some following episodes,

remaining his identity veiled. Then the mourners go to Parnell's

grave. When Jack Power mouths the superstitious hope, which is prevailed

as a rumor through the novel, that "one day he will come again," Hynes,

whose poem proclaimed that he would "Rise, like the Phoenix from the flames"

(D120)25 now retorts, "Parnell will never come again.... Peace

to his ashes" (U06.924-27): he has changed.26

The rattle of pebbles halts him. He peers down into a stone crypt

and sees an obese gray rat wriggling under the plinth. He imagines

the rat devour a corpse gluttonously. When he discovers a Robert

Emery's grave, he recalls the dubious rumor that the remains of Robert

Emmet(1778-1803), an Irish patriot who recklessly attempted to get Napoleon's

assistance for an Irish rebellion and was brutally hanged in public(U06.977-78).27

Finally he goes through the gates, relieving himself from memories of his

father's and his son's death, the images of corpse-hunting and human bodies'

rotting: "Back to the world again. Enough of this place" (U06.995-96).

The mystical journey of the personal crisis and complicated visions of

his incursion to "another world" are reserved for the adventure in Nighttown

in the 15th episode "Circe."

III : Joyce's Plan in Manuscripts

According to the chronology Richard M. Kain gives in Dublin in the Age

of William Butler Yeats and James Joyce, the period between 1914 and 1922

was very bloody and severe in Ireland struggling with the British Empire

for independence: World War I, the Easter Rising, the Anglo-Irish War and

the Irish Civil War occurred during that time:

|

|

|

|

|

Estimated 85,000 in Ulster Volunteers, 132,000 in Irish. Declaration of war postpones application of Home Rule, splits Irish Volunteers, the extreme nationalists, 10,000, electing Professor Eoin MacNeilll head, October. Secret council of Irish Republican Brotherhood plans rising. |

|

|

Parades and maneuvers in Dublin. |

|

|

Easter Rising, April 24-30. Fifteen executed, May 3-12; deportation of 1,700 to English prisons; trial and execution of Roger Casement, August; release of prisoners, December. |

|

|

Sinn Fein wins Parliamentary seats.Sinn Fein Convention, October 25-27, replaces Griffith with de Valera and adopts more Republican stand, De Valera is elected head of Volunteers, making him leader of both Republican organizations. |

|

|

Parliament votes conscription for Ireland, April 18; widespread protests; suppression of meetings and arrest of de Valera, Maud Gonne MacBride, Griffith, and others for presumed "German plot," May 17. |

|

|

First Dail meets in Dublin, January 21, declares independence, elects de Valera president, Cathal Constabulary opens war. De Valera escapes from prison, February 3, goes to United States (June 1919-December 1920). Terrorism increases. |

|

|

Increasing violence with arrival of "Black and Tans," March; hunger strike, Mountjoy Prison, Dublin, April; Terence MacSwiney, lord mayor of Cork, becomes a national hero, dying in Brixton Jail, London, October 25, after seventy-four-day hunger strike. Collins directs counterespionage. Griffith and MacNeill arrested, November 26. Cork burned, December 11, damage of L3,000,000.English Parliament passes Government of Ireland Act, providing for two Irish parliaments, one to meet in Belfast (six counties), the other in Dublin (twenty-six counties). |

|

|

Elections for Parliaments called for in Government of Ireland Act, May 24. Treaty signed in London, December 6: dominion status and partition. Treaty debates split Dail. |

|

|

Treaty ratified, 64-57, January 9; de Valera resigns presidency, loses re-election, 58-60. Southern Ireland has four "governments": Dail (Griffith, president), the allied Provisional government under Michael Collins, the disaffected Republicans under de Valera, and the army under Rory O'Connor. O'Connor's troops seize Four Courts as headquarters, April 13. Arthur Griffith dies, August 12, and Michael Collins is killed, August 22. Free State established, December 6. |

(193-98, abridged)28

In 1906, while working on stories which would later be published in Dubliners,

Joyce told his brother Stanislaus, that he was considering one, to be called

"Ulysses," that would involve a Jewish Dubliner, Alfred H. Hunter, whom

Stanislaus, in conversation with Richard Ellmann in 1954, remembered that

he was rumored to have an unfaithful wife.29 At that time,

Joyce did not proceed to write this story. It was not until 1909

when Joyce began to gather detailed information and make notes for Ulysses

as a new novel, as he later remarked in his letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver

dated 8 November 1916.30 A firmer beginning date is early

1914 when he was in Trieste, as he appended the date to the text.

Thanks to John Quinn, the Irish-American lawyer in New York and patron-collector

of modern art and literature and Ezra Pound, Ulysses appeared in

both magazines, The Little Review in New York and The Egoist in

London, thus earning a double fee for Joyce who had permanent financial

trouble. So serial publication began in The Little Review

in March 1918, while Pound warned Joyce on Good Friday that censorship

was necessary, and needed changes and deletions for much lascivious and

sexual material for The Egoist : he removed the reference to the dog pissing

in the 3rd episode "Proteus" and Bloom's toilet scene in the 4th episode

"Calypso," etc. Then the 2nd episode "Nestor," the 3rd episode "Proteus,"

and portions of the 6th episode "Hades," and the 10th episode "Wandering

Rocks" appeared in The Egoist between January and December 1919,

after which, with opposition stirring, the magazine itself ceased publication.

The Little Review serialization continued more or less peacefully until

December 1920 when the final part of the 14th episode "Oxen of the Sun"

was published. As is well-known, the other episodes 15-18 were not

published in any magazine serially. Concerning the 6th episode

"Hades," the fair manuscript called "Rosenbach Manuscript" were sent to

be typed to H.S. Weaver, 18 May 1918. The typescripts were sent to

Weaver and Pound prior to 29 July 1918: it was published in The Little

Review, September 1918.31

After the initial publication in the magazine, Joyce never ceased numerous

additions and emendations until it was finally published as Ulysses

by Shakespeare and Company in 1922. Even after the first edition

of Ulysses was published in 1922, he continued to check typographical

errors until 1932 when the final versions for Joyce were made with the

assistance of Stuart Gilbert for the first Odyssey Press edition.32

Joyce in the European Continent naturally felt the gloomy atmosphere caused

by World War I, and continued to insert and correct a number of phrases

in Ulysses. The manuscript and the typescripts extant for the "Hades"

episode are:

|

|

|

|

|

|

MS (Rosenbach Manuscript) 40 leaves | ------- |

|

|

The Little Review (September 1918) | ------- |

|

|

TS (Buffalo V.B.4) | JJA12.273-84 |

|

|

Placard 10 First version | JJA17.203-10 |

|

|

Placard 10 Second version | JJA17.211-19 |

|

|

Placard 11 First version-1(dated 10 April 1921) | JJA17.220 |

|

|

Placard 11 First version-2 | JJA17.221-28 |

|

|

Placard 11 Second version | JJA17.229-36 |

|

|

Placard 11 Third version | JJA17.237-44 |

|

|

Placard 12 First version-1(dated 11 April 1921?) | JJA17.246 |

|

|

Placard 12 First version-2 | JJA17.247-54 |

|

|

Placard 12 Second version | JJA17.255-62 |

|

|

Placard 12 Third version | JJA17.263-70 |

|

|

Page Proofs; Gathering 6 First version | JJA22.318-26 |

|

|

Page Proofs; Gathering 6 Second version(dated 21 September 1921) | JJA22.334-46 |

|

|

Page Proofs; Gathering 6 Third version(dated 27 September 1921) | JJA22.350-62 |

|

|

Page Proofs; Gathering 6 Fourth version(dated 1 October 1921) | JJA22.366-78 |

|

|

Page Proofs; Gathering 7 First Version | JJA22.381-95 |

|

|

Page Proofs; Gathering 7 Second version | JJA22.397-411 |

|

|

Page Proofs; Gathering 7 Third version | JJA22.413-27 |

|

|

Ulysses (first edition, 1922; 1932) | ------ |

*Placards (Harvard, Buffalo V.C.4; not reproduced: Harvard, Buffalo V.C.4);

JJA17.202-70.

**Page Proofs (Buffalo V.C.1, Texas; not reproduced: Baffalo V.C.1-2);

JJA22.317-427.

These

are the only existing records we can trace as to how the episode was made.

Of course, the date of the making of this episode's framework was earlier:

between 1914 and 1918. The Rosenbach MS and the Little Review

version are almost the same, and were written in mid 1918. We can't

specify on which dates most of the TS, the Placards and the Page Proofs

were made, though they were doubtlessly between 1918 and 1922, when Ireland

struggled with the British Empire. Most of the insertions in the

later levels were employed unchangeably to the 1922 edition: doubtlessly

he made uncountable extinct noteslips for them and well considered before

they were added.

Most of

the insertions in this episode seem to add a far gloomier atmosphere.

Why did Joyce intensify it so extensively, although this episode deals

with the cemetery scene? The following chart shows extracts of the

inserted dark impressions after the Little Review version(about

65% of all the insertions):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Got off lightly with illness compared. Scarlatina, influenza epidemics. Canvassing for death. Don't miss this chance. | death + medicine |

|

|

|

To the inexpressible grief of his. After a long and tedious illness. | medicine |

|

|

|

Rattle his bones. Over the stones. Only a pauper. Nobody owns. | death + medicine (anatomy) |

|

|

|

Rattle his bones. | death + medicine (anatomy) |

|

|

|

So much dead weight. Felt heavier myself stepping out of that bath. | death |

|

|

|

Seat of the affections. Broken heart. | death + "organ" |

|

|

|

Come forth, Lazarus! And he came fifth and lost the job. | religion (resurrection) |

|

|

|

Even Parnell. Ivy day dying out. | death + nationalism |

|

|

|

[---Parnell will never come again, he said.] Peace to his ashes. | death + nationalism |

|

|

|

Ireland was dedicated to it or whatever that. Seems anything but pleased. Why this infliction? | nationalism |

|

|

|

Cremation better. Lethal chamber. Ashes to ashes. Or bury at sea. Where is that Parsee tower of silence? Eaten by birds? | death + religion (Catholicism ) |

|

|

|

Laying it out. Molly and Mrs Fleming making the bed. Pull it more to your side. Our windingsheet. Never know who will touch you dead. | death + sex |

|

|

|

Thy will be done. A dying scrawl. | death /life |

|

|

|

On whose soul Sweet Jesus have mercy. | death + religion |

|

|

|

[and he was landed up to the father on the quay] more dead than alive. | death /life |

|

|

|

Kicked about like snuff at a wake. | death /life |

|

|

|

[---But the worst of all, Mr Power said, is the] suicide > man who takes his own life. | death (suicide)/life |

|

|

|

They have no mercy on that here or infantcide. Refuse christian burial. They used to drive a stake of wood through his heart in the grave. As if it wasn't broken already. Yet sometimes they repent too late. Found in the riverbed clutching rushes. He looked at me. | death + religion (Catholicism)+ "organ" |

|

|

|

The Mater Misericordiae. Eccles street. My house down there. Big place. Ward for incurables there. Very encouraging. Deadhouse handy underneath. Where old Mrs Riordan died. They look terrible the women. Her feeding cup and rubbing her mouth with the spoon. Then the screen round her bed for her to die. Nice young student that was dressed that bite the bee gave me. He's gone over to the lying-in hospital they told me. From one extreme to the other. | death + medicine (hospice) |

|

|

|

Dead meat trade. Byproducts of the slaughterhouses for tanneries, soap, margarine. | death (slaughter) + anatomy |

|

|

|

Murder. The murderer's image in the eye of the murdered. They love reading about it. Man's head found in a garden. Her clothing consisted of. Recent outrage. The weapon used. Murderer is still at large. Clues. A shoelace. The body to be exhumed. Murder will out. | death (murder) + violence (terrorism/ nationalism) |

|

|

|

Requiem mass. Crape weepers. Blackedged notepaper. Your name on the altarlist. | religion(Catholicism) |

|

|

|

More dead for her than for me. | death |

|

|

|

Widowhood not the thing since the old queen died. Drawn on a guncarriage. Victoria and Albert. Frogmore memorial mourning. But in the end she put a few violets in her bonnet. Vain in her heart of hearts. All for a shadow. Consort not even a king. Her son was the substance. Something new to hope for not like the past she wanted back, waiting. It never comes. | death + nationalism (anti-Britain) + "organ" |

|

|

|

[Father Coffey. ...] With a belly on him like a poisoned pup. | death (poison) |

|

|

|

Burial friendly society pays. Penny a week for a sod of turf. | religion (Catholicism) |

|

|

|

Death by misadventure. | death (accident) |

|

|

|

Very encouraging. Our Lady's Hospice for the dying. | death + medicine (hospice) |

|

|

|

[They drove on] past Brian Boroimhe house. | nationalism |

|

|

|

It's all the same. Pallbearers, gold reins, requiem mass, firing a volley. Pomp of death. | death + nationalism? |

|

|

|

---I was for the races, Ned Lambert said. > --- I was down there for the Cork park races on Easter Monday, Ned Lambert said. *Allusion to the Easter Rising? | nationalism? |

|

|

|

Will o' the wisp. Gas of graves. | death |

|

|

|

Tell her a ghost story in bed to make her sleep. Have you seen a ghost? Well, I have. It was a pitchdark night. The clock was on the stroke of twelve. | death |

|

|

|

You might pick up a young widow here. Men like that. Love among the tombstones. Romeo. | death/sex |

|

|

|

More room if you buried them standing. Sitting or kneeling you couldn't. | death |

|

|

|

It's the blood sinking in the earth gives new life. Same idea those jews they said killed the christian boy. | death(murder) + religion(resurrection) / Jewishness |

|

|

|

By carcass of William Wilkinson, auditor and accountant, lately deceased, three pounds thirteen and six. With thanks. | death + medicine |

|

|

|

Rot quick in damp earth. | death + anatomy |

|

|

|

Daren't joke about the dead for two years at least. Go out of mourning first. | death + religion (superstition) |

|

|

|

Read your own obituary notice they say you live longer. Gives you second wind. New lease of life. | death + religion (superstition) |

|

|

|

[... after he died] through he could dig his own grave. We all do. Only man buries. No, ants too. First thing strikes anybody. Bury the dead. | death + religion |

|

|

|

Only a mother and deadborn child ever buried in the one coffin. | death |

|

|

|

Then darkened deathchamber. Light they want. Whispering around you. Would you like to see a priest? Then rambling and wandering. Delirium all you hid all your life. The death struggle. Devil in that picture of sinner's death showing him a woman. Dying to embrace her in his shirt. Last act of Lucia. Shall I nevermore behold thee? Bam! He expires. Gone at last. | death/sex + anatomy |

|

|

|

They ought to have some law to pierce the heart and make sure or an electric clock or a telephone in the coffin and some kind of a canvas airhole. | death + "organ" |

|

|

|

Who kicked the bucket... Eulogy in a country churchyard it ought to be that poem of whose is it Wordsworth or Thomas Campbell. Entered into rest the protestants put it. Old Dr Murren's. The great physician called him home. Well it's God's acre for them. | death + religion (Protestantism) |

|

|

|

Earth, fire, water. Drowning they say is the pleasantest. See your whole life in a flash. But being brought back to life no. Can't bury in the air however. Out of a flying machine. | death + religion (superstition) |

|

|

|

Underground communication. We learned that from them. | death/life |

|

|

|

Flies come before he's well dead. | death + anatomy |

|

|

|

[Last time I was here was Mrs Sinico's funeral.] Poor papa too. The love that kills. And even scraping up the earth at night with a lantern like that case I read of to get at fresh buried females or even putrefied with running gravesores. | death/sex + anatomy |

|

|

|

I will appear to you after death. You will see my ghost after death. My ghost will haunt you after death. There is another world after death named hell. I do not like that other world she wrote. No more do I. | death/life + sex? + religion(superstition) |

|

|

|

Habeas corpus. | *At this level, Joyce also added many other detailed descriptions.death |

|

|

|

Standing? His head might come up some day above ground in a landslip with his hand pointing. | death + anatomy |

|

|

|

De mortuis nil nisi prius. | death + superstition |

|

|

|

The Irishman's house is his coffin. | death + nationalism? |

|

|

|

Death's number. | death + religion |

|

|

|

God idea a postmortem for doctors. Find out what they imagine they know. He died of a Tuesday. | death + medicine(anatomy) |

|

|

|

[Mr Bloom walked unheeded along his grove] by saddened angels, crosses, broken pillars, family vaults, stone hopes praying with upcast eyes. | death + religion |

|

|

|

After dinner on a Sunday. Put on poor old greatgrandfather. Kraahraark! Hellohellohello amawfullyglad kraark awfullygladaseeagain hellohello amawf krpthsth. | death + anatomy |

|

|

|

It might thrill her first. Courting death. | death + sex |

|

|

|

The one about the bulletin. Spurgeon went to heaven 4 a.m. this morning. 11 p.m. (closing time). Not arrived yet. Peter. | *Reference to James Stephens? |

|

|

|

Hoping you're well and not in hell. Nice change of air. Out of the fryingpan of life into the fire of purgatory. | death/life + religion |

|

|

|

One, leaving his mates, walked slowly on with shouldered weapon, its blade blueglancing. | violence [nationalism?] |

|

|

|

[Mr Bloom walked unheeded along his grove...], old Ireland's hearts and hands. | nationalism |

|

|

|

Priests dead against it. Devilling for the other firm. Wholesale burners and Dutch oven dealers. | death + religion (Catholicism) + anatomy |

|

|

|

Plant him and have done with him. Like down a coalshoot. Twentyseventh I'll be at his grave. Ten shillings for the gardener. He keeps it free of weeds. Old man himself. Bent down double with his shears clipping. Near death's door. | death (fertility) |

|

|

|

Smith O'Brien. Someone has laid a bunch of flowers there. Woman. Must be his deathday. For many happy returns. *At this level J added more detailed information of the city centre. | death + nationalism (+ medicine?) |

|

|

|

Dead side of the street this. Dull business by day, land agents, temperance hotel, Falconer's railway guide, civil service college, Gill's, catholic club, the industrious blind. Why? Some reason. Sun or wind. At night, too. Chummies and slaveys. Under the patronage of the late Father Mathew. Foundation stone for Parnell. Breakdown. Heart. | *New ref. to Sackville Street. (allusion to Easter Rising?) death + nationalism + "organ" |

|

|

|

Shuttered, tenantless, unweeded garden. Whole place gone to hell. Cf.U06.001-12. | death (murder) |

|

|

|

How she met her death. | death |

|

|

|

[Must be careful about women.] Catch them once with their pants down. Never forgive you after. | death/sex |

|

|

|

We obey them in the grave. | death |

|

|

|

Tomorrow is killing day. | death (slaughter) |

|

|

|

A lean old ones tougher. | death + anatomy |

|

|

|

Wait, I wanted to. I haven't yet. *Inserted Bloom's will to live. | life |

|

|

|

Callboy's warning. Near you. | *Adds Seduction to death? death |

|

|

|

Drawn on a guncarriage. [Victoria and Albert.] | *Allusion to the Irish wars? nationalism (anti-Britain) + violence |

*"LINE

NO." is based on the "Main Text" (the Gabler edition). See my Notes.

As

this analysis proves, Joyce inserted many references to death after publishing

the Little Review version of this episode. Most of them are

inserted to intensify the theme of this episode, "going to Hades," so it

is quite natural that Joyce added more images of death, sometimes from

the view of anatomy. But at the stage of the Little Review version,

it already had enough atmosphere which expresses the tour to Hades.

Why did Joyce add these extra images of death to it? Probably Joyce

satirized the series of struggles between Ireland and the British Empire,

by adding the nationalistic descriptions and more death images to this

episode.

For

instance, Joyce emended at Level 09 :"---I was for the races, Ned

Lambert said. >--- I was there for the Cork park races on Easter Monday"

(U06.558). As the above chronology shows, Cork was a very

important place for the struggle, especially in 1921 when Joyce emended

this sentence, and the Easter Rising broke out on Easter Monday, April

24, 1916. Moreover at Level 14 he added the paragraph which begins

with "Dead side of the street this" (U06.316-20), which refers to

Upper Sackville Street near the GPO, the headquarters of the rising.

Joyce, who seemingly pretended not to be interested in politics and continued

to describe old Dublin when he lived there, secretly depicted the Dublin

after the Easter Rising in his novel. The phrase "I am the resurrection

and the life" (U06.670) reminds us of James Stephens's The Insurrection

in Dublin, the famous journalistic record of the Easter Rising. He

wrote "I remained awake until four o'clock in the morning"33

on the first day in the insurrection and on the second day, "At eleven

o'clock the rain ceased, and to it succeeded a beautiful night, gusty with

wind, and packed with sailing clouds and stars. We were expecting

visitors this night, but the sound of guns may have warned most people

away."34 These times curiously coincide with the above

insertions on Level 13, "The one about the bulletin. Spurgeon went

to heaven 4 a.m. this morning. 11 p.m.(closing time). Not arrived

yet. Peter" (U06.787-89). In Finnegans Wake, the

word "Surrection" appears once (FW593.02-3) which, as James Fairhall explains,

is used in connection with the Easter Rising.35 The word

"resurrection" also connotes "insurrection" in this episode.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the reason why Joyce described the details of the streets

of Dublin and the dark side of the reality of death persistently is, as

he said, that if Dublin was destroyed, it can be possible to rebuild it

by looking at this novel. Probably he did not describe Lower Sackville

Street on a purpose, because he knew that the street he was familiar with

was already completely destroyed when he was writing Ulysses.

He appears to have virtually ignored the Easter Rising and the subsequent

series of Irish wars for establishing the Free State. But it is ridiculous

to think that Joyce is not a nationalist only because his attitude toward

Irish nationalism is obscure in his works. One may say that his nationalism

had disappeared with Parnell's death which is described and alluded to

in many parts of his works. He satirizes the struggle by intensifying

the death imagery in the episode of death.

The

most famous episode dealing with the theme of Irish nationalism in

Ulysses

is the 12th episode "Cyclops," set in Barney Kiernan's pub where Bloom

is attacked by "the citizen."36 Needless to say, the

prototype of "the citizen" is Michael Cusack (1847-1907), founder of the

Gaelic Athletic Association and member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood,

and that the latter underground organization secretly plotted the 1916

Rebellion.37 The next episode "Aeolus" starts with "IN

THE HEART OF HIBERNIAN METROPOLIS" making us conscious of the downtown

area where the revolt occurred. In Finnegans Wake, there is

a ballad "THE BALLAD OF PERSSEE O'REILLY" (FW044.23-47.29) which brings

to mind both Patrick Pearse and Michael Joseph O'Rahilly, fallen heroes

of the Easter Rising.38

Unlike

W.B. Yeats, Sean O'Casey and other Irish writers, Joyce never explicitly

referred to the Easter Rising and the Irish wars for independence.

But it seems to me as if Joyce had thought a "Good puzzle would be to depict

early 20th-century Dublin without passing on nationalism."

Unlike the Dantean Inferno, dead Irish heroes were implicitly mentioned

in the "Hades" episode.

Notes

Main

Text: Joyce, James. Ulysses. London: The Bodley Head, 1986.

All citations from this are referred to in the following style:

Ux.y [x = the episode number, y = the line number in each episode].

Sub

Texts: 1) Gen. ed. Groden, Michael. The James Joyce Archive (or JJA),

vols.12, 17&22. New York & London: Garland Publishing, 1978.

2) Joyce, James. "Ulysses": A Facsimile of the Manuscript I.

London: Faber and Faber in association with The Philip H. &

A.S.W. Rosenbach Foundation, Philadelphia, 1975.

3) Joyce, James. "Ulysses V." The Little Review, vol.V, no.5

(September 1919), pp.15-37.

1

Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of "Ulysses" and Other Writings

(Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1989), p.69.

2

Stuart Gilbert, James Joyce's "Ulysses": A Study (New York: Vintage

Books, 1955),

p.159. There are two different schemata: the Gorman-Gilbert schema and

the Linati

schema. Cf. Richard Ellmann, Ulysses on the Liffey (New York:

Oxford University,

1972), pp.186-87.

3

Ellmann, Appendix.

4

It begins at 10 p.m. according to the Gorman-Gilbert schema, but the delivery

scene

is around 11 p.m. Cf. Gilbert, p.294 and Ellmann, Appendix.

5

Gilbert, p.168.

6

Mark Osteen, The Economy of "Ulysses": Making Both Ends Meet

(New York:

Syracuse University, 1995), p.100.

7

Cf. Osteen, p.159.

8

Cf. R.M. Adams, "Hades" (Ed. Clive Hart and David Hayman, James Joyce's

"Ulysses":

CriticalEssays. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), pp.92-93.

9

Clive Hart and Leo Knuth, A Topographical Guide to James Joyce's "Ulysses"

(Colchester: A Wake Newslitter Press, 1981), MAP III.

10

Homer,

The Odyssey (trans. E.V. Rieu. London: Penguin Books, 1946),

p.266.

11

Cf. Don Gifford with Robert J. Seidman, "Ulysses" Annotated: Notes for

James

Joyce's "Ulysses"(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988),

p.109: "6.222.

Smith O'Brien."

12

Cf. Gifford, p.110: "6.264-65. Reuben J and the son." In real life

Dodd was not a

Jewish.

13

Cf. D.J. Hickey and J.E. Doherty, A Dictionary of Irish History 1800-1980

(Dublin:

Gill and Macmillan, 1987), pp.143-46.

14

James Fairhall, James Joyce and the Question of History (Cambridge:

Cambridge

University Press, 1993), p.109.

15

Budgen, p.69.

16

Cf.

U06.759. Cf. also Gifford, pp.111-12: "6.334. In the midst

of life."

17

The Dublin Cemeteries Committee, The Dublin Cemeteries: Prospect (Glasnevin)

and Goldenbridge 1829-1906 (or DCPG)(Dublin: Dollard, Printinghouse,

1906), p.13.

In this book, we can check that Rev. Francis J. Coffey, C.C.(acting chaplain)

and

John O'Connell (superintendent) actually worked at the cemetery around

1904.

18

Dublin Cemeteries Committee, Glasnevin Cemetery: An Historic Walk

(Dublin:

Glasnevin Cemeteries Group, 1997), p.5.

19

Cf. DCPG, p.156.

20

Cf. DCPG, pp.161-62.

21

Cf. DCPG, pp.167-68.

22

Cf. Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1982), p.136.

Actually Joyce's mother May Joyce died on August 13, 1903, at the early

age of

forty-four. Mrs. Joyce's body was taken to Glasnevin to be buried,

and John

Joyce wept inconsolably for his wife and himself. "I'll soon be stretched

beside

her," he said, "Let Him take me whenever he likes" (136).

23

Cf. Douglas Bennett, Encyclopaedia of Dublin (Dublin: Gill

and Macmillan,1991),

p.85:"Glasnevin Crematorium Ltd."

24

Cf.

U 05.172-73.

25

Ed. John Wyse Jackson and Bernard McGinley, James Joyce's "Dubliners":

An

Annotated Edition(London: Sinclair-Stevenson,1993).

26

Cf. U12.1538-39. Cf. also Osteen, p.164.

27

Gifford, p.124: "6.977-78. Robert Emery. Robert... wasn't he?"

28

Richard M. Kain, Dublin in the Age of William Butler Yeats and James

Joyce

(Devon, Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1972).

29

Ellmann,

James Joyce, p.230.

30

Ed. Stuart Gilbert, Letters of James Joyce, vol.I (New York: The

Viking Press,

1957), p.98.

31

Cf. James Joyce, "Ulysses": A Facsimile of the Manuscript, " Dates

Relevant to

the Composition of Each Episode."

32

Cf. Clive Driver, James Joyce "Ulysses": A Facsimile of the Manuscript,

Biblio-

graphical Preface, p.32.

33

James Stephens, The Insurrection in Dublin (Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire,

1992; originally published in 1916, Dublin), pp.19-20.

34

Stephens, p.30.

35

Fairhall, p.54. Cf. James Joyce, Finnegans Wake (New York:

Penguin Books,

1976).

36

Cf. Eishiro Ito, "The Nameless Narrator and Nationalism: A Study of the

'Cyclops' episode of Ulysses" (The Harp or IASIL-JAPAN

Bulletin, vol.XII,1997),

pp.103-12.

37

Cf. Emer Nolan, James Joyce and Nationalism (London: Routledge,1995),

p.87.

38

Fairhall, pp.231-32.